Whisking Around

What the heck is whisking?!

You might immediately think of whisking as something you do when you're baking and mixing dry ingredients, but whisking is also the fastest known movement made by mammals.

Let's first set the stage: all mammals—with the exception of duck-billed platypus, echidna, and humans—have whiskers. And, even in humans, 35% of all people have vestigial whisker muscles in their upper lips.

In fact, whiskers are an defining feature of the mammal kingdom, and it's thought that whiskers developed when our mammalian ancestors first arose during the time of dinosaurs. These early mammals couldn't rely on their eyes because they came out at night to avoid being eaten by dinosaurs.

A whisker is a sensory hair which is highly specialized for picking up information about an animal's environment and sending signals to its brain. You can think of a whisker as a needle on a record player that reads surface irregularities that are then turned into meaningful music.

Technically, these long, stout hairs are known as vibrissae (from the word "vibrate"), with vibrissae on the face being called whiskers, but in common usage all vibrissae are referred to as whiskers.

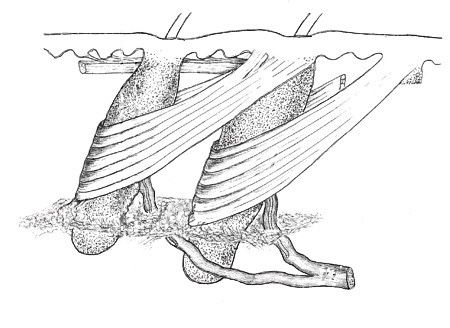

Like other hairs on a mammal's body, whiskers are made of keratin and contain no nerves; but, unlike hairs, the follicle at the base of every whisker is surrounded by special nerve cells, and every cell connects to a far greater number of eight different kinds of receptors that send nerve impulses to the brain.

Microscopic shifts in the direction, velocity, and duration of a whisker’s movements build a map of where an animal's body is positioned in space, what shapes and textures it is touching, how fast things are moving around it, what route to take, and so much more.

Many mammals have several hundred nerve cells connected to the base of each whisker. Rats and mice, for example, have about 25,000 nerve cells associated with their whiskers, which enables them to detect even the most minute details of their environment.

But, if that sounds amazing, consider seals and sea lions, who have 10x more nerves.

Every whisker on a seal or sea lion has 1500 nerve cells, and the whiskers on their heads have a total of 300,000 nerve cells. So highly attuned are these whiskers that seals and sea lions can detect the turbulence left by a fish that swam by minutes earlier, and they can then track that fish like a dog following a scent trail. Seals can not only detect a fish swimming 300 feet away, but even tell what species it is, or at least determine its size and the direction it's heading.

There are many, many more examples of how animals use whiskers—shrews that determine whether something is food or not food with a single touch, dolphins that use whisker follicles to detect the electric fields of their food, etc—but let's close out by returning to the idea of whisking.

A wide variety of smaller mammals, such as rats, mice, shrews, porcupines, opossums, flying squirrels, and hamsters, are considered whisker specialists because they have tiny bands of muscle wrapped around the base of each whisker. These muscles move each whisker independently back and forth 3-25 times per second; this process is called "whisking," and it's the fastest known movement in the mammal kingdom.

Whisker specialists are essentially using their whiskers like fast-moving fingers to touch and analyze every part of their environment at extremely high speeds. In fact, rats and mice use whisking to test the ground at every footstep and they only put their front feet down in spots that have already been scanned by their whiskers.

So, take another look at the whiskers on your cat or dog, admire how they're neatly arranged on the animal's snout, cheeks, eyebrows, and legs, and think about how they are a critical part of this animal's sensory world.

Member discussion