The River's Liver

If you think of a river, you might imagine a fast-moving body of water flowing effortlessly over a rocky bed. But if you're a fan of this newsletter, you can guess that there's a bigger story here!

This week's topic arose out of a conversation with poet Kim Stafford in response to my recent newsletter on Boundary Layers. Kim mentioned his fascination with the hyporheic zone, and coincidentally I had just read about this topic in a book by Ellen Wohl. Kim proposed renaming this zone "ghost river," and the next morning he wrote a poem that sent me down the rabbit hole of this week's newsletter.

You might not realize this, but the visible surface waters we see in a river are moving quickly and that's a big problem for rivers. Riffles, rapids, and turbulence stir oxygen into the water so it's oxygen-rich, but at the same time the water is a relative dead zone because it's either nutrient-poor or else the nutrients are flowing downstream and out of the system. Then, if you dig down, the bed of rocks, mud, and debris that a river sits on are also largely devoid of life.

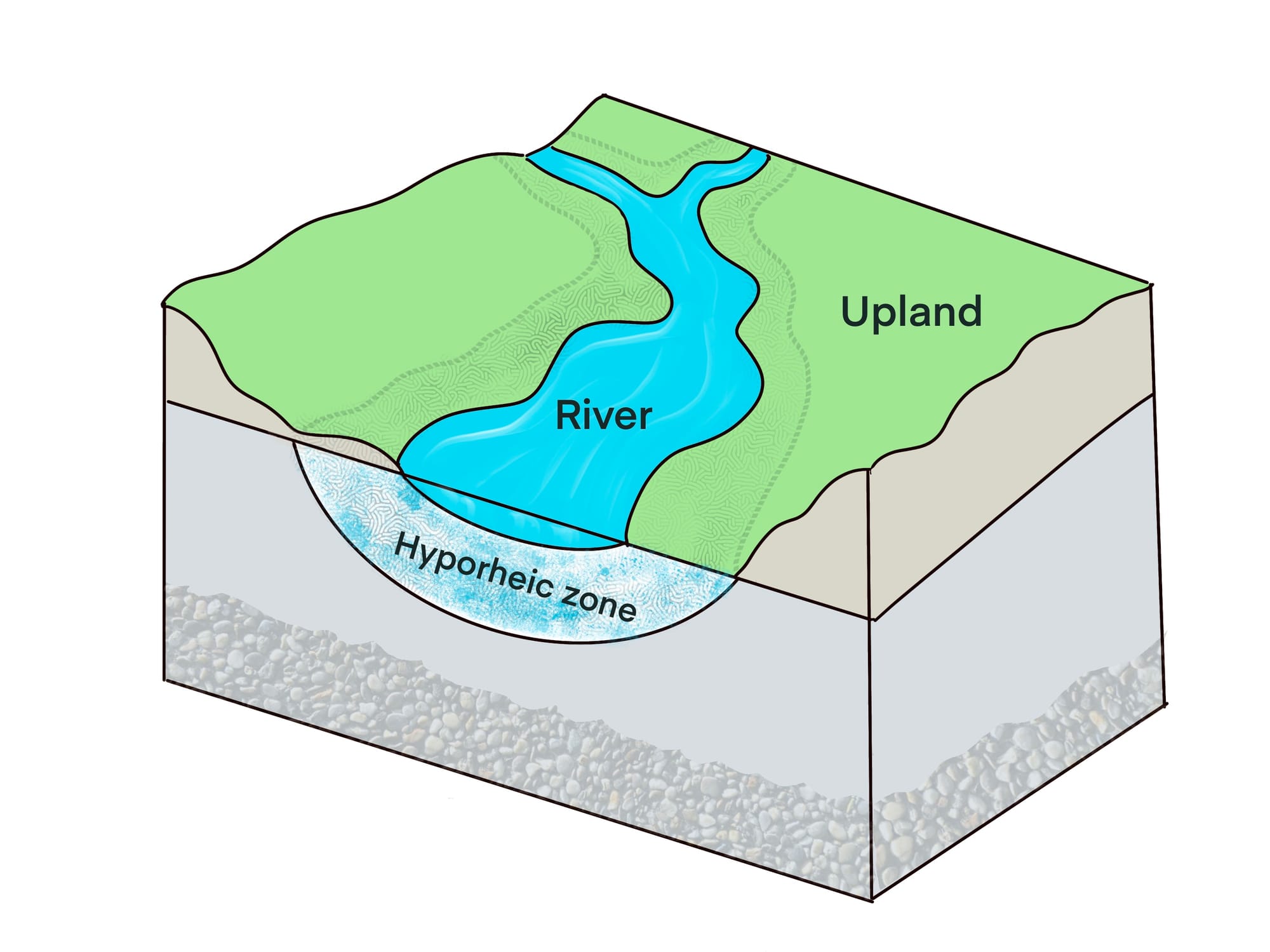

Yet between the two extremes of water and rock, there is an interface (or an ecotone) called the hyporheic zone. This zone is so important it is often called the river's liver, or the river's gut, because it is the area where a river processes nutrients and regulates its health.

In essence, the visible river we see on the surface is merely one portion of a much larger body of water with profound implications for the life of the river itself.

The hyporheic zone is created when water flowing downstream encounters obstacles or changes in elevation that "pump" water into surrounding materials with hydraulic pressure. This pumping can be so extensive that the true shape of the river may extend dozens of feet downward, and outward up to a mile from the river into the surrounding landscape.

As Kim Stafford writes, this hyporheic zone is essentially a hidden ghost river, a sister river that expands outward to fill and flow through the empty underground spaces between gravels and loose soils alongside the visible river.

By definition, water in the hyporheic zone is still considered part of the river because it flows directly out of the river channel then returns within minutes, hours, or days as the changing shape of the landscape "pumps" water back into the channel. This bi-directional flow in and out of the river channel is critical because it mixes oxygen from surface water with nutrients and minerals from the ground.

Equally important, water speed slows dramatically in the hyporheic zone, giving microorganisms and invertebrates a stable place to live while they capture passing nutrients and build complex food webs that we never see when we peer into a river. In fact, nearly all of a river's microbes and invertebrates are found in this zone, hidden from sight.

The hyporheic zone was first discovered and researched in the context of salmon redds, the unique places where salmon lays eggs in river gravels. Salmon choose to lay their eggs in, and their larvae grow up in, the exact locations where the hyporheic zone is pumping water back into the channel because these are areas where the current is both slower and richest with oxygen and nutrients.

Biologists subsequently discovered that hyporheic zones can be easily lost or irreparably damaged when rivers are modified to fit human needs, and this led to a new science of river restoration. [Here is a fascinating account of the first attempt to restore the hyporheic zone in a damaged urban stream.]

We need ghost rivers because they keep waterways healthy by pumping oxygen and nutrients in and out of the water, while also regulating the biological and chemical processes that occur in a river. What's amazing is that all of these extraordinarily complex mechanisms happen out of sight, beyond the edges of the rivers we see.

[If you want to learn more, check out this short entry from Wikipedia, or this long highly technical review of the scientific literature.]

Member discussion