The Conifer Advantage

If you drive long distances across northern or western North America, you might find yourself wondering why there are endless stands of conifers stretching to every horizon. Winter is the key to understanding why there are so many conifers here.

Winter Ecology Talk

Today's topic is inspired by a talk on winter ecology I'll be offering in support of the North Cascades Institute on January 22. In this talk we'll discuss the dynamics of snow and ice and how this shapes the lives of plants and animals. Please join me for this fascinating online presentation.

Trees are unique plants to the extent that they invest considerable energy into building massive structures and living very long periods of time. However, one drawback to this investment is that trees cannot migrate with the seasons, like animals do, nor can they die back and survive harsh conditions as seeds or roots like wildflowers and smaller plants do.

Instead, trees are locked in place and must face challenging conditions that arise over the course of years and centuries.

Plants require water for photosynthesis so the availability of water over the seasons goes a long way towards explaining why conifers dominate in western North America where summers are mostly bone dry. While deciduous trees only have leaves in the summer and struggle to survive summer droughts, conifers keep their leaves (needles) year-round and wait until rain starts falling in the fall, winter, and spring to do all their photosynthesizing.

Because conifers are only minimally active during the dry summer months, the key factors that give them an advantage occur during the winter, and we can start with their characteristic, spire-like appearance.

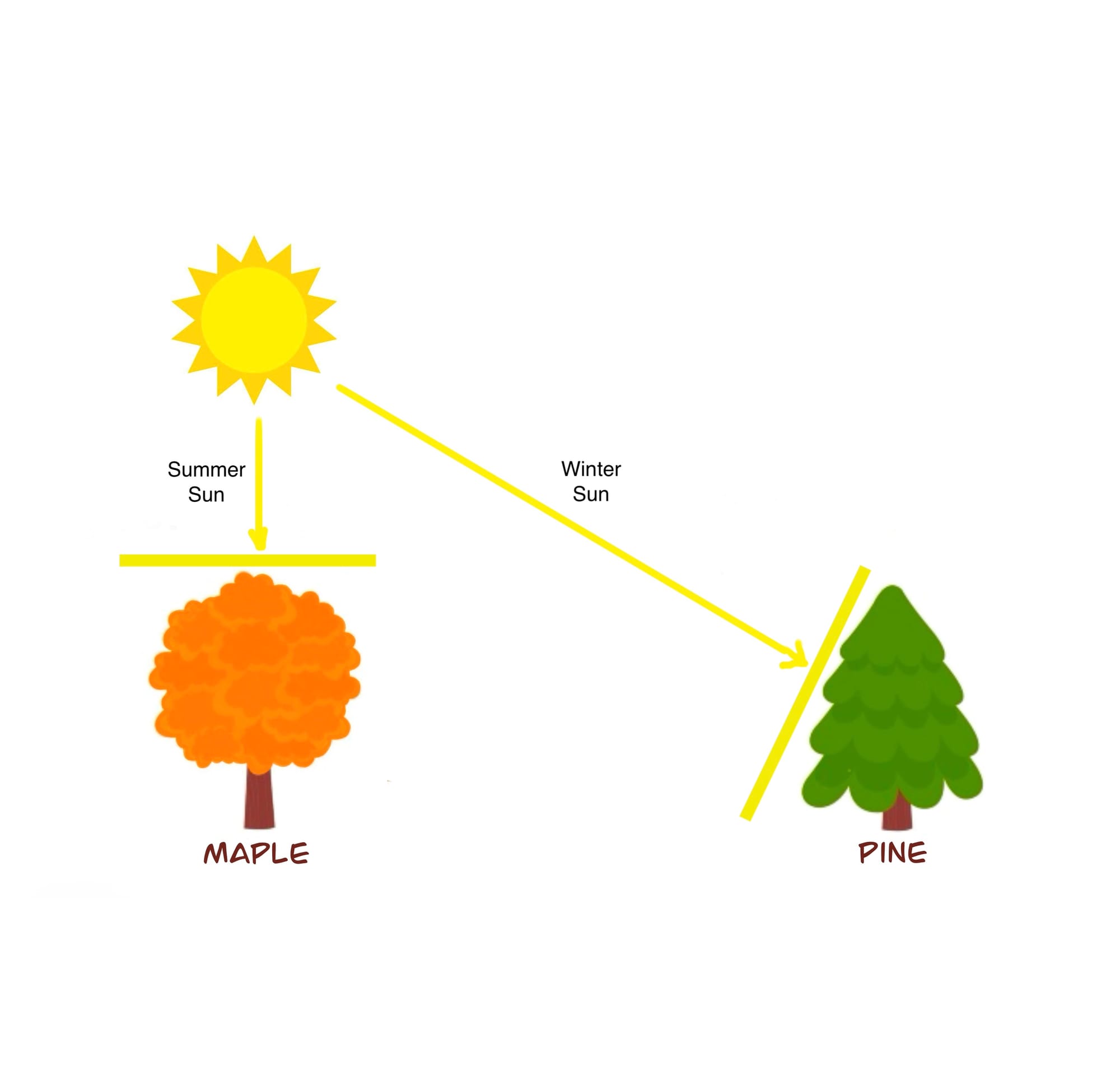

Trees that photosynthesize in the summer, such as maples and oaks, have rounded, umbrella-like shapes designed to capture sunlight energy as the sun passes directly overhead. In the winter, however, the sun is low on the southern horizon, and it turns out that the tapering crowns of conifers are perfectly angled to capture this low sun. Not only do conifers have crown designed for the low light of fall, winter, and spring, but their needles are photosynthetically active at this time of year as well.

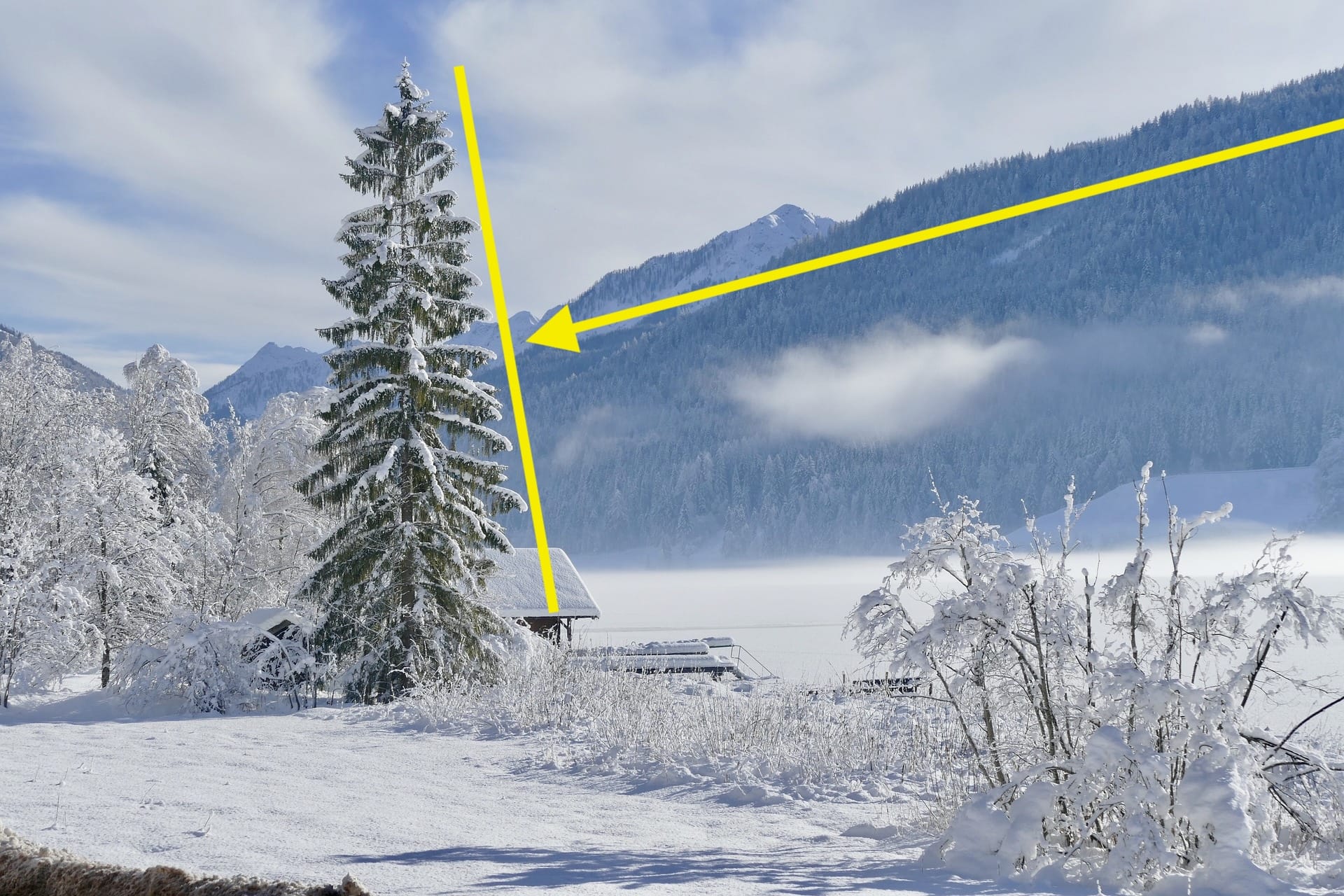

However, if you hold onto your leaves through the winter then you must deal with extreme cold, ice, and heavy snow. Fortunately, conifer needles are protected by a shiny, waxy cuticle that snow and ice doesn't easily stick to, and their narrow, spire-like crowns shed snow like very steep roofs.

This generally keeps snow from accumulating on conifer trees and breaking off branches, but conifer wood is also very flexible and composed of long fibers so if conifers get covered in snow, they can bend over then spring back without being harmed.

Perhaps the biggest threat to any tree or plant during winter is the risk that freezing temperatures will turn the water inside their cells into ice. Again, conifers have many adaptations at their disposal.

First of all, plants can survive their tissues being frozen if they can control where the freezing takes place. Conifers do this by moving water out of their cells into the many empty spaces located throughout their needles. This allows freezing to take place outside the cells, and as this water turns into ice it releases latent heat which helps prevent the remaining water inside the cells from freezing.

Finally, having needles that survive harsh winters and remain on the tree for up to 15 years means that conifers don't need a lot of nutrients to grow a new crop of leaves every spring. This proves to be a critically important advantage in northern and western North America where rocky, nutrient-poor soils are the norm.

We tend to overlook the distinctive Christmas tree-like shape of conifers but look again because it's a highly specialized design perfectly suited for the environments where these trees thrive.

Member discussion