Standing on Toes

It's fun to consider this obvious fact: birds spent most of their lives in the air, which means their legs and feet are their primary point of contact with the earth and serve a critical role.

If you look closely at the legs and feet of a bird you can spot prominent clues into how that bird lives its life. For example, a duck's feet are modified to support walking, swimming, and landing, while a hawk's feet are designed for perching and grabbing prey.

But behind this simple observation, what's really going on with those awkward looking legs that birds have?

One of the first things I notice when I look at the picture above is how gnarled and scaly this vulture's feet look. Yes, those horny scales provide protection for one of the only spots on a bird where its bare skin is exposed to the elements, but these scales also highlight the surprisingly close link between birds and reptiles. I mean, really, look at those legs; they belong on a reptile!

I also notice the toe arrangement, which is three toes pointing forward and one toe pointing to the rear. In essence, a bird has opposable toes for gripping branches in the same way that humans have opposable thumbs for picking up and manipulating small objects.

But this is just part of the picture, because the toes that a bird is standing on are the endpoint of a very long foot that starts at that odd, backward-bending "knee" on a bird. This backward bend on a bird's leg is actually an ankle, while the knee itself is hidden higher up in feathers against the body.

Because a bird's body is designed for flight, it follows a very simple design principle: all of a bird's weight is positioned around its center of gravity.

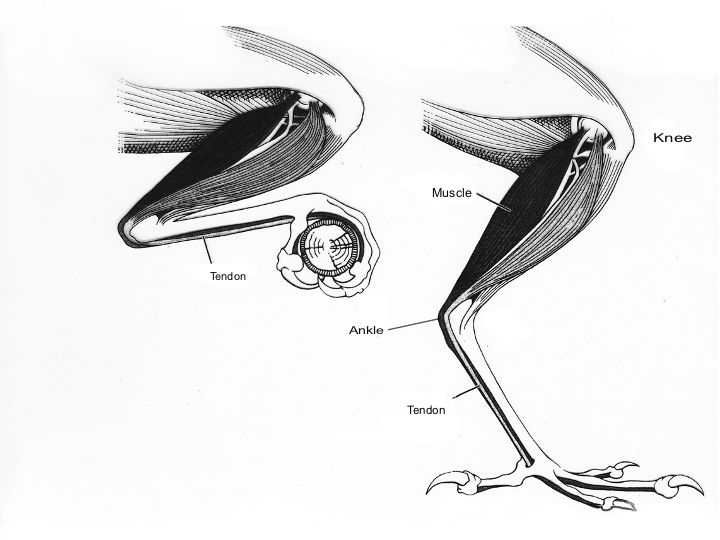

This means that a bird's massive leg muscles are located high on its leg, close to the center of gravity, while the rest of their long, lanky leg is controlled by thread-like tendons on a pulley system.

You can clearly see this arrangement of muscles and tendons in this marvelous illustration by Katrina van Grouw (make sure you check out her incredible book The Unfeathered Bird by Princeton University Press!).

This system of muscles and tendons is an extremely elegant solution for the problem of how to control a long limb without adding long heavy muscles, but it has another fascinating benefit.

If look at the long, slender tendon that starts high up on the leg, below the knee, you'll see that it extends downward behind the backward-bending ankle then attaches to the tip of each toe.

When a bird stands on a perch, then squats down, its leg bends backwards at the ankle, stretching and pulling the main tendon. This pulls on the tendons extending to the tips of each toe, and closes the foot without needing any muscles to grip the branch!

(If you'd like to learn more about bird legs and feet, check out my short talk on my Video tab above.)

Member discussion