Standing on Ice

As humans, we cocoon ourselves within (and can only tolerate) a narrow range of temperatures. Animals don't always have this luxury, but they have some fascinating adaptations for dealing with extreme temperatures.

You might say that one "core" concept of animal metabolism is the necessity of maintaining a sustainable core body temperature. And this is true whether you're a cold-blooded animal (poikilotherm) whose body temperature mirrors external temperatures, or a warm-blooded animal (homeotherm) who regulates its body temperature by burning calories.

While essential for all animals, controlling this balance becomes exponentially more difficult when the outside environment reaches extreme temperatures because an animal would die if it were forced to maintain the same core temperature in all parts of its body during extreme heat or cold.

Because we're in the middle of winter and I'm watching animals walking on snow and ice, I'm thinking today about how animals deal with extreme cold.

And, since it's cold outside, let's consider the impact of cold on an animal's extremities. Think about how the extremities that are furthest from the body's core, like our fingers and toes, get stiff and cold when we're in the snow.

Humans suffer and quickly lose the ability to move our fingers when we get too cold, but an animal in the wild couldn't survive if it lost its ability to move its legs, ears, or tail every time if got cold.

The only options for an animal are to transfer heat to its extremities—which is energetically expensive and unsustainable because the heat would be quickly lost to the environment—or to develop alternate strategies.

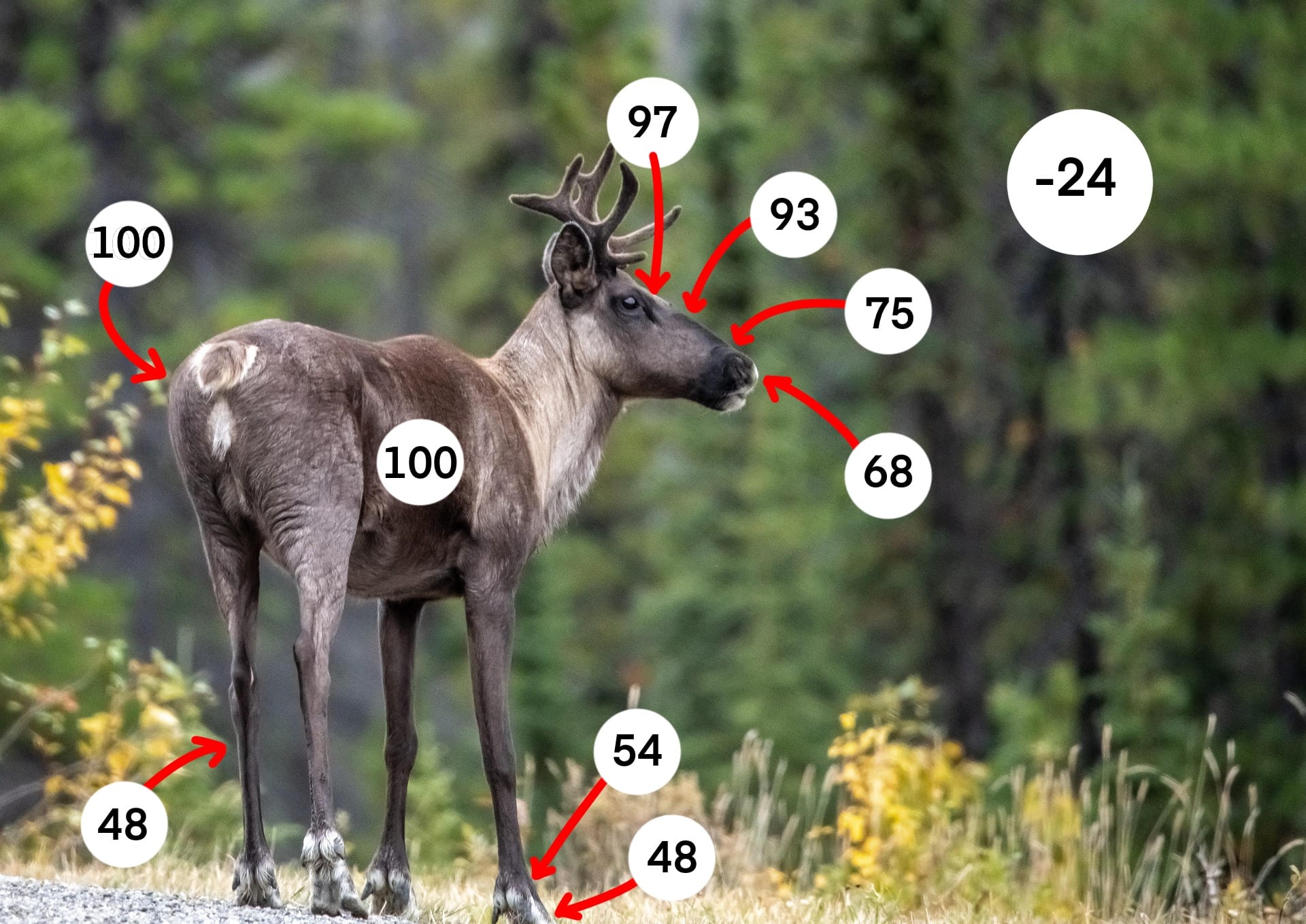

Many animals (and more are being discovered all the time) practice a strategy known as regional heterothermy. In other words, animals keep different parts of their bodies at different temperatures.

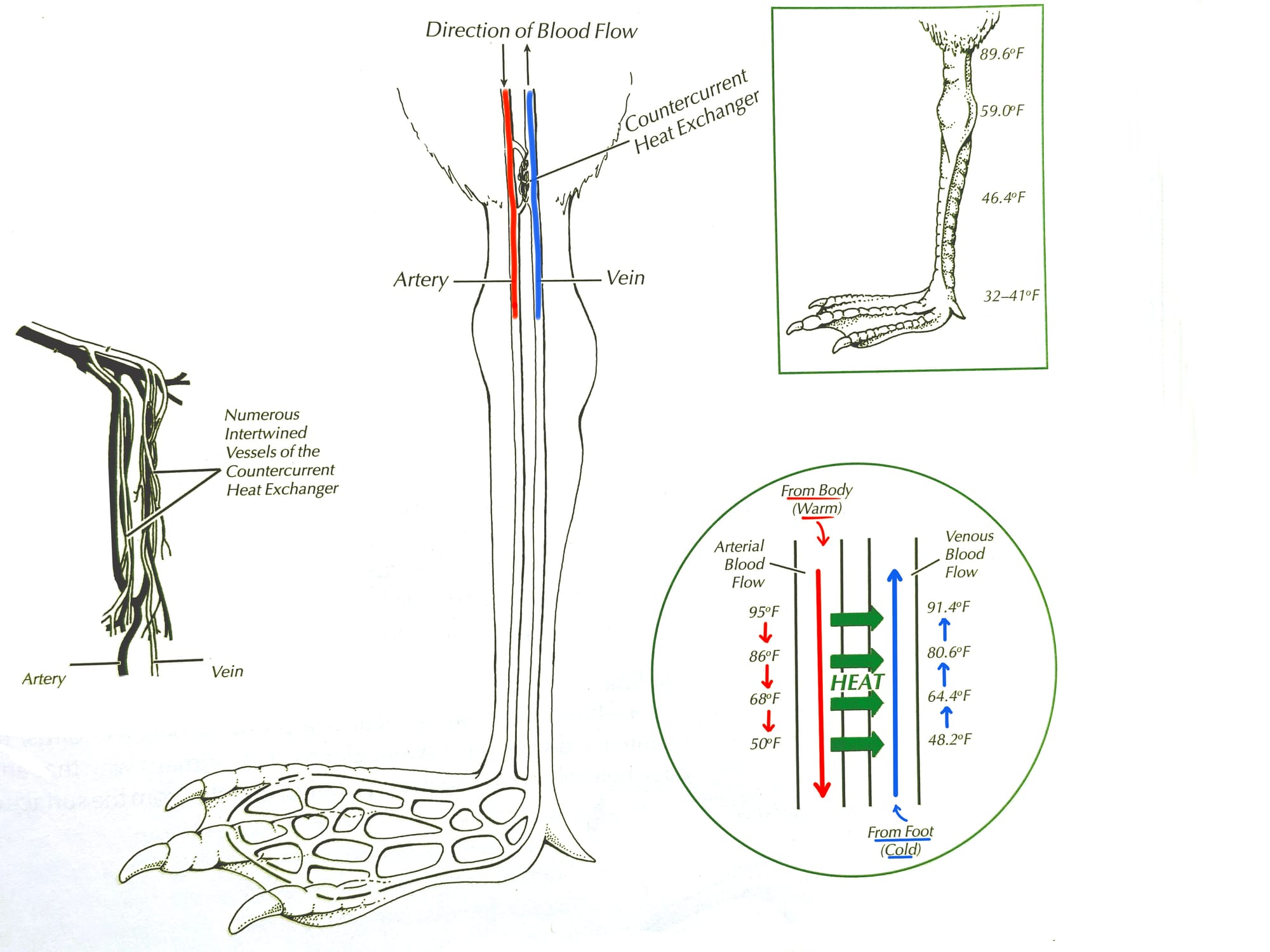

The classic example of regional heterothermy is a bird standing on snow or ice. Birds clearly don't try to keep their naked legs and feet warm all day long, nor do their legs and feet freeze. Instead, birds have an elegant countercurrent exchange system, whereby the arteries carrying hot blood from their bodies mingle closely with the veins carrying cold blood from their feet back to their heart.

In a countercurrent exchange system, precious heat from a bird's core is not sent directly to its feet, where it would be immediately lost to the environment, but is instead used to warm up cold blood flowing from the feet back into the bird's core. This means that slightly warmed blood keeps their feet from freezing, and it means that chilled blood isn't flowing to their hearts and compromising their core body temperature.

Regional heterothermy has been documented in many other animals including deer, dogs, sea turtles, tuna, sharks, whales and dolphins, snakes, lizards, sea stars, and bumblebees. For example, a deer cannot heat its feet in the winter, or its hooves would melt into the snow, and it couldn't walk.

In addition to regional heterothermy, where an animal maintains different temperatures in different parts of its body, some animals also practice temporal heterothermy, when they heat their bodies to different temperatures at different times of the day or year.

Ultimately, these strategies are ways to regulate body temperatures in a range of challenging conditions, but I hope you'll think about regional heterothermy the next time you feel a dog's cold nose, or feel your fingers start to go numb in the snow!

Member discussion