Shattered Raindrops

An astonishing variety of insects, birds, plants, and animals have some type of waterproof covering on their outer surfaces. In fact, these water-resistant features are ubiquitous in the natural world and critical for the survival of organisms, but have you ever wondered what's going on here?

Let's begin by asking why plants and animals want to repel water in the first place? In part, the answer is because if water sticks around it will probably spread out as a thin film over every available surface, and a film of water on your outer surfaces can cause some serious issues.

For example, a film of water on a plant's leaves will dramatically reduce its ability to exchange gases during photosynthesis. For flying birds and insects, the extra weight and aerodynamic burden of water means they would not be able to fly. And animals of all types will experience significant heat loss when they were wet.

Another serious issue is that pathogenic bacteria and fungi readily germinate and grow in the presence of water, which means that if you remain wet you'll become covered in rapidly growing colonies of tissue-eating or disease-causing microorganisms.

But think about what we observe in the real world: raindrops falling from leaves, water rolling off the backs of birds, tiny droplets of moisture briefly appearing on the back of a beetle. In all of these cases, these plants and animals have some kind of oily or waxy coating (like we do on our waterproof coats) and it's easy to assume that the coating is what keeps them dry.

However, a team of scientists started looking more closely at this question and made a fascinating discovery that changes how we think about the behavior of raindrops.

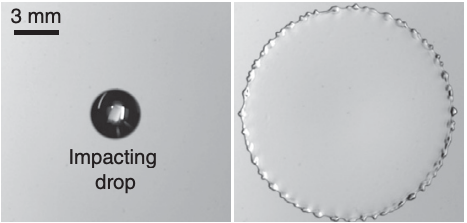

As a point of comparison, let's begin by visualizing what happens when a raindrop lands on a piece of hydrophilic glass (a special type of glass that attracts and retains water). In this setting a raindrop responds by simply spreading outward with a rapidly expanding rim.

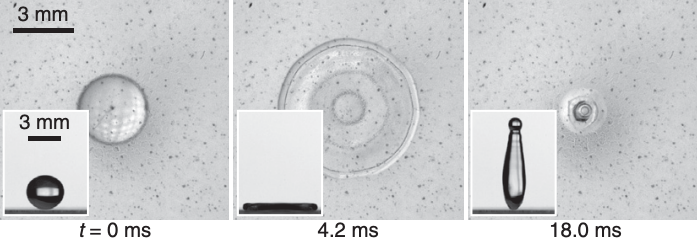

However, on a superhydrophobic glass surface that repels water, a raindrop exhibits a different type of behavior. It first begins to expand outward, but then it pulls back, and shoots upward in a pillar.

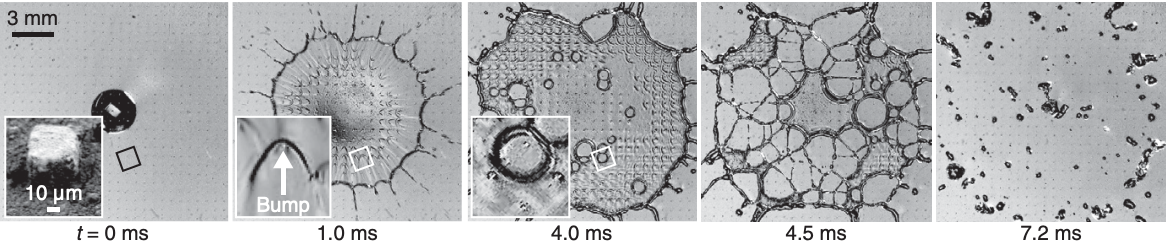

What's mind-boggling is how plants and animals have tweaked their outer surfaces to achieve an entirely different result. Instead of simply repelling water with oils or waxes, many plants and animals have added infinitesimally tiny microscale and nanoscale structures (i.e. bumps and other three-dimensional shapes) to the surfaces of their leaves, shells, scales, exoskeletons, and feathers. These unique features don't simply shed water but instead cause raindrops to shatter upon impact (I'll include a short video at the end showing what this looks like).

This has several profound implications. Notice that in the example with the superhydrophobic glass the water droplet lingers for 18.0 milliseconds, but only 7.2 milliseconds when tiny structures cause the droplet to explode. This is more than a two-fold reduction in the amount of time that water lingers on the surface, which means water won't have a chance to stick around and seep into cracks and pores between cells where it would start causing issues.

These powerful explosions of water also play a critical role in washing away contaminating particles of dirt, pollen, and bacterial or fungal spores that might otherwise stick around and start growing.

In other words, there is a lot more going on with waterproof surfaces in the natural world than you probably realized!

Examples of water droplets exploding on plant and animal surfaces (clicking this link takes you the Lukas Guides website where it plays in the newsletter there). Film clips from Seungho Kim, Zixuan Wu, Ehsan Esmaili, Jason J. Dombroskie, and Sunghwan Jung

Member discussion