Overly Prescribed

Language has the capacity to be a playful, ever-shifting creation, but we are taught—and most of us believe—that words must obediently follow rules governing sentence structures, meanings, and spellings.

If you make a mistake, or step out of bounds, countless self-appointed language experts will promptly push you back into safe terrain and scold you for your errors.

Given this backdrop and training, it might surprise you to learn that these ideas about language represent only one small blip in the long and rich history of the English language.

English is a mongrel language, first arising as Germanic peoples invaded the British Isles, and then morphing many times under the influence of Scandinavian, Latin, and French speakers.

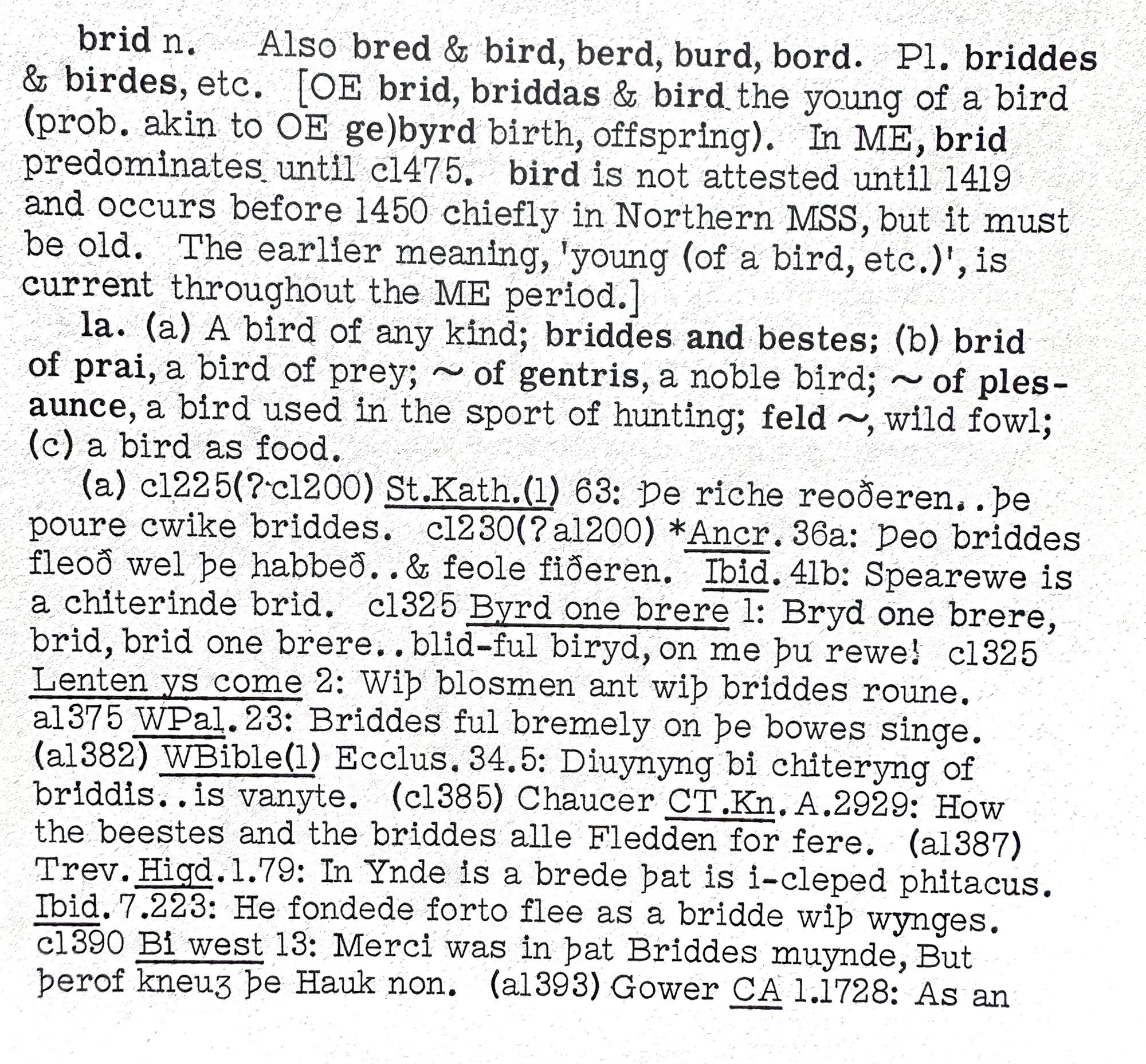

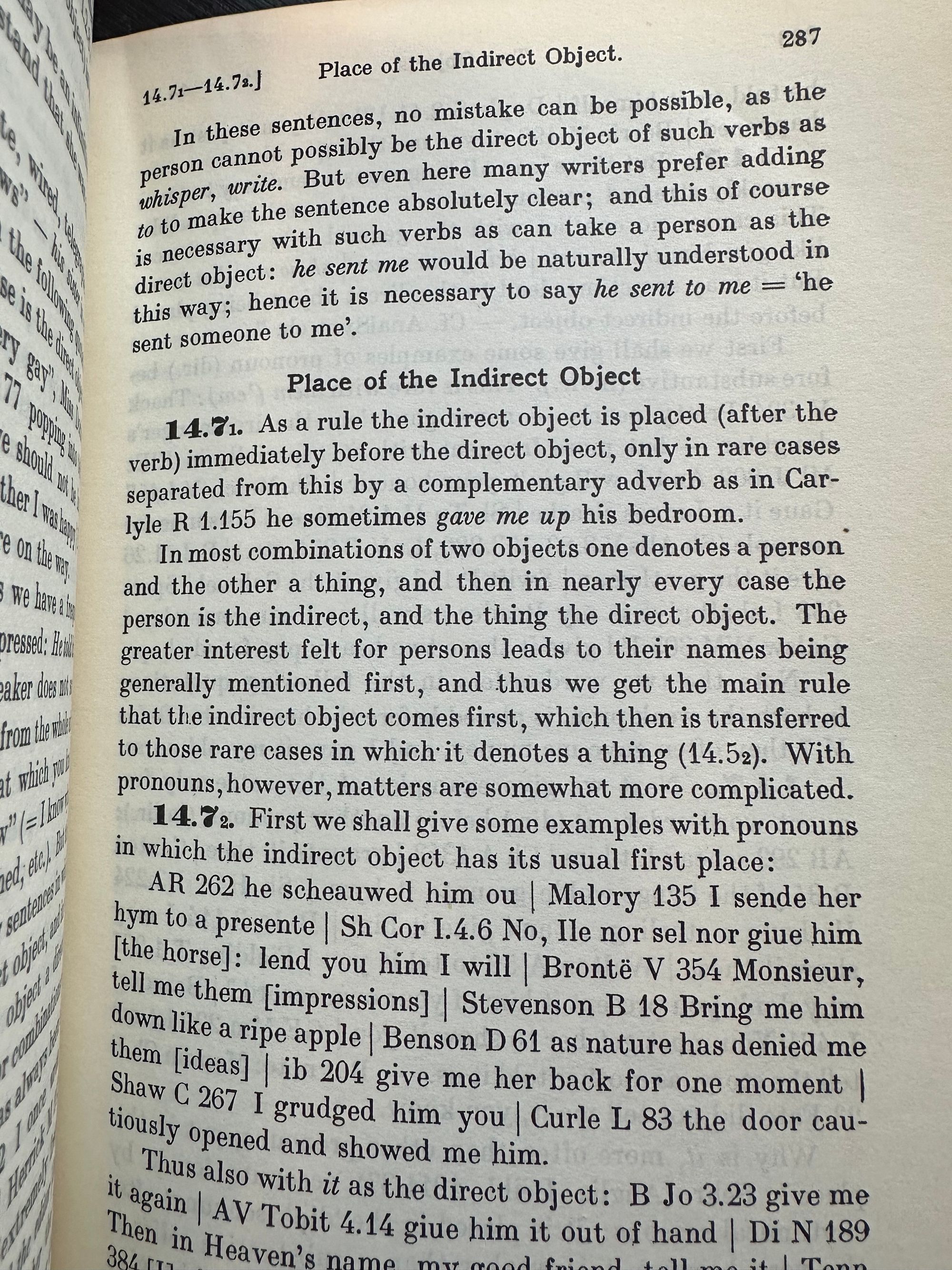

By the end of the 1400s, the phase of English known as Middle English was a marvelously inventive carnival of colliding and merging languages. There could be 50 versions of the same word and there was no set rules for how words were spelled, defined, used, or pronounced.

Personally, I think that Middle English was the heyday of the English language—but it was also generally acknowledged that things were a bit of a mess.

What happened next can only be described as an overcorrection.

In the 1700s, a group of elites known as the Prescriptivists started creating rules for how words should be spelled, used, and pronounced.

Many of these rules were arbitrary and not based on how English was used by people at that time, which meant that you would only know these rules if you belonged to an elite, ruling class, or if you were trained at an elite school.

The problem with these rules is that they were immediately used as a tool for marginalizing anyone who belonged to another culture, another social class, or did not fit the norm.

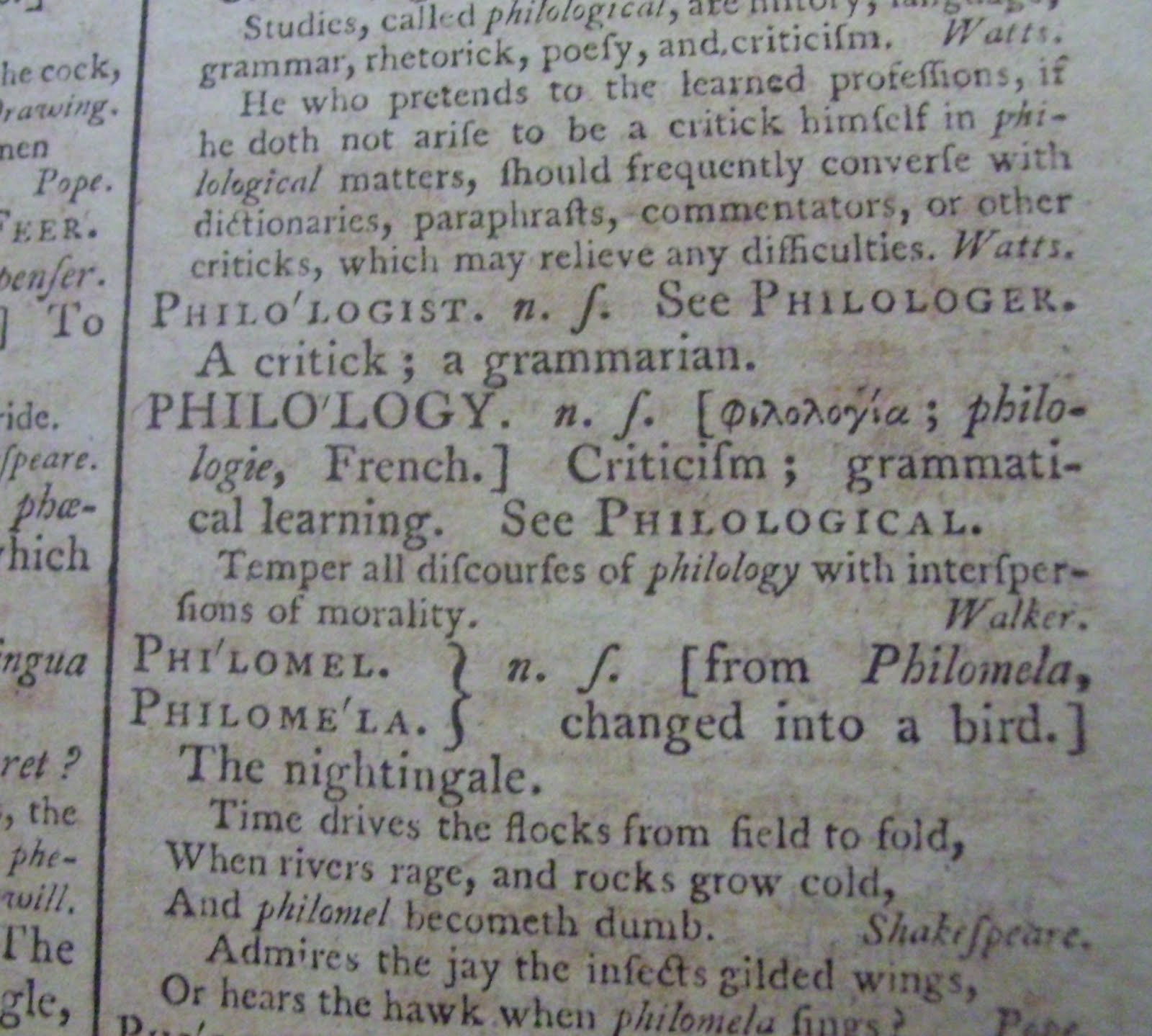

For example, Samuel Johnson, who published the first standardized dictionary for the English language in 1755, declared that everyone who used spellings he didn't approve of were "ignorant barbarians."

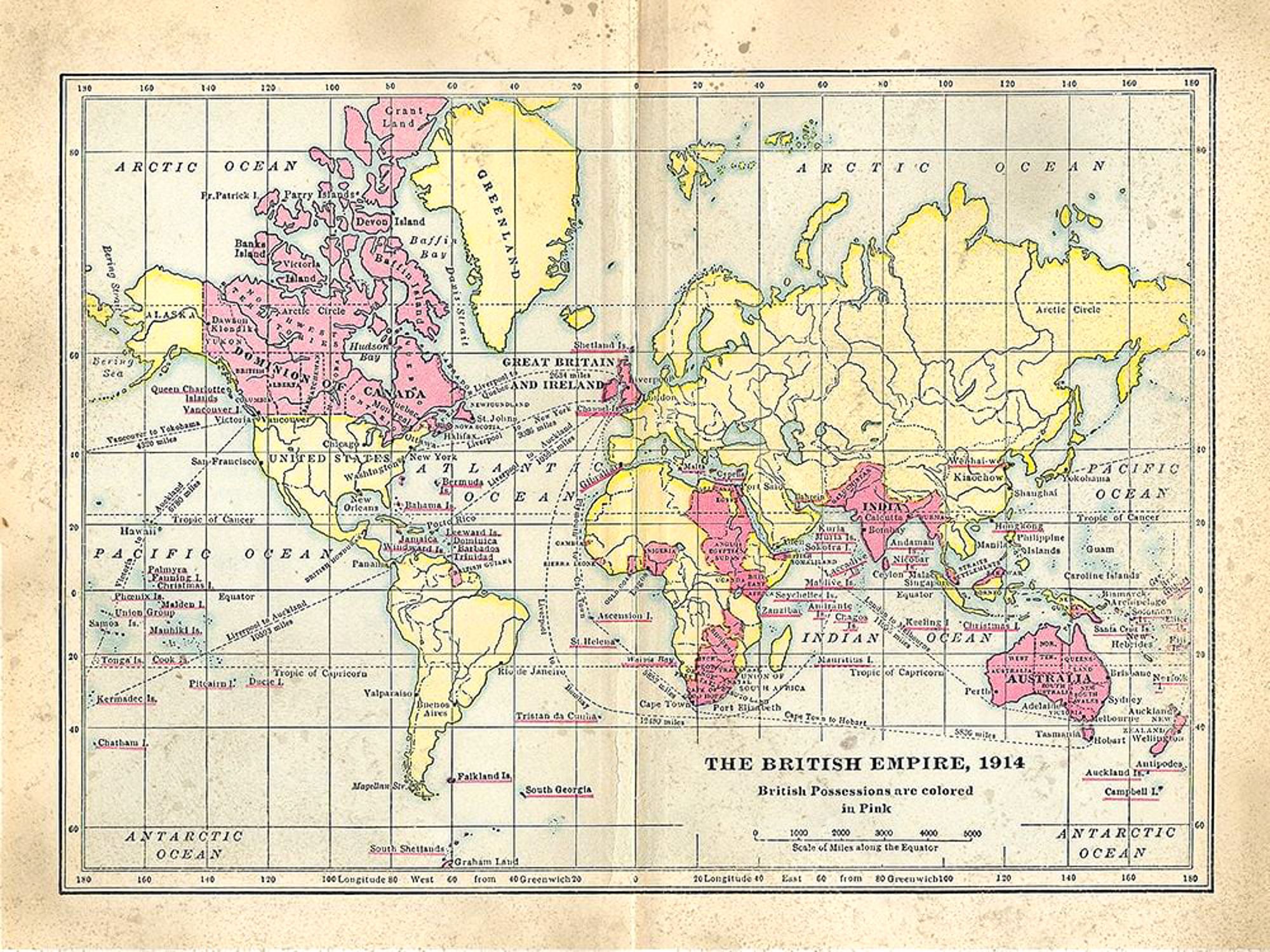

The overt agenda of what came to be known as Prescriptivism was proving that the version of English created by a single, ruling class was the only civilized, God-given form of English, and that the "legitimacy" of Standard English could then be used to justify England's massive colonial empire.

What I find fascinating about this history is that we are now so deeply embedded and trained in this way of thinking that we blindly follow and enforce these rules without noticing either how these rules marginalize other voices or how they stifle the creative power of language.

Clearly, there are times when it's appropriate and efficient to use language that is standardized and easily understood.

But language also needs the freedom to be wildly creative, and take unexpected leaps of the imagination—and this is when too many rules can get in the way.

Member discussion