Of Chittediddles & Hackmatacks

In 1804, Lewis and Clark started up the Missouri River on a journey of epic proportions. Their task—given to them by President Thomas Jefferson—was to cross the continent, home to dozens of diverse (and sometimes unfriendly) native tribes, and document a place largely unknown in the European imagination.

Barely six months earlier, Jefferson had purchased the 580-million acre Louisiana Territory from France, an immense area in the middle of the United States, but no one had a clear idea of what lay in this vast and utterly wild landscape.

Without question, the story of Lewis and Clark's two-year journey to the Pacific Ocean and back is a tale of great hardship and deprivation, but what's less often appreciated is the truly epic linguistic challenge they faced.

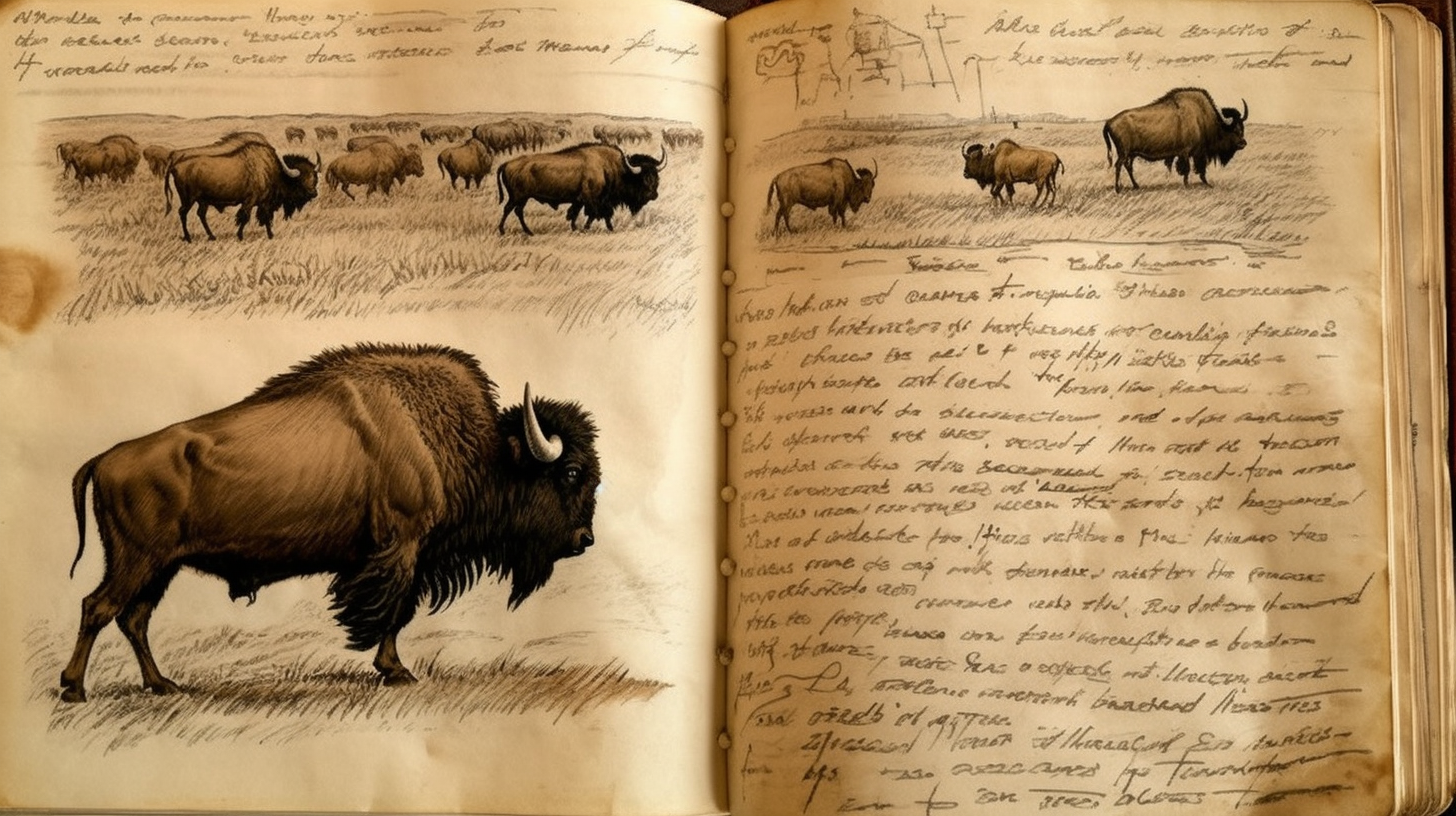

Imagine the task—and awesome responsibility—of having to name every plant, animal, tribe, cultural custom, and geologic feature on a two-year expedition where everything is new to you.

This was an especially daunting task because Lewis and Clark had rudimentary grade school educations (which was typical at the time), almost no scientific training, and very little worldly experience to draw from. To name this ever-changing landscape, day after day, meant they had no choice but to resort to their imagination and use whatever crude materials they had on hand.

What's particularly charming and useful about their efforts is the sincere and unpretentious way they approached this enormous undertaking. Their writing wasn't filtered through the lens of education, so more than any other piece of American literature, the Lewis and Clark journals capture the raw character of life beyond the edge of the frontier.

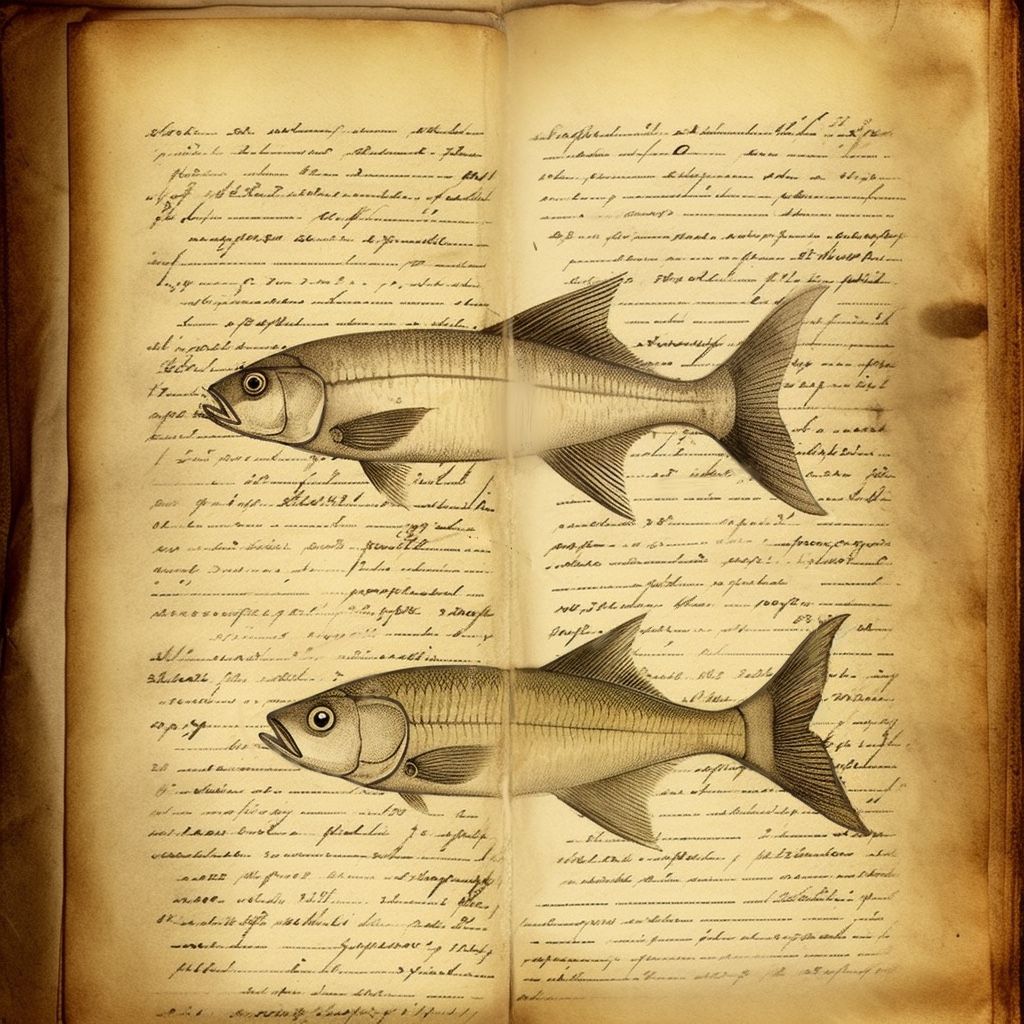

Faced with the task of naming countless things that no European had ever witnessed, Lewis and Clark were forced to invent words, combine words from the languages they were encountering, and use familiar English words in utterly new ways. Many of the words that came easiest to Lewis and Clark were old colloquial and dialectical words they grew up with in the backwoods of Virginia, so their journals are full of intriguing new formations like chittediddle (katydid) and hackmatack (western larch).

It's even more fascinating that at that time there were no standardized spellings, so Lewis and Clark often wrote out words phonetically, mimicking the sounds they were hearing when illiterate fur trappers or Native American translators gave them names for things. This gives us an immensely valuable glimpse into how words were spoken at a time when these wildly different cultures were mingling and uncomfortably clashing on a continent in flux.

It is said that in the course of describing this vast wilderness Lewis and Clark added 1500 new words to the English language. Many of these words are so commonplace today that we take them for granted, but names like "mule deer" and "grizzly bear" and "prairie dog" had to be invented from scratch by Lewis and Clark.

This is language in its most vital state, when everything is fresh and new. Today we have stifling grammatical rules, old dictionaries, and critical spell checkers looking over our shoulders. We forget that language is also meant to be wildly fertile and playful, that we are meant to break rules in order to speak of experiences that matter to us...just like Lewis and Clark.

Lewis and Clark witnessed herds of buffalo that took hours to pass, flocks of birds darkening the skies, animals that had no fear of humans, unmarred vistas which stretched for hundreds of miles, and proud, vibrant native cultures in their prime. It's inconceivable to imagine what that experience must have been like. It's inconceivable to imagine what it would take to name this experience.

Member discussion