Microbaroms and Giant Fipples

At this exact moment, a massive shift of energy and biomass is happening on the Earth's surface as billions upon billions of birds undertake epic migrations in response to the changing seasons.

The question of how birds, and especially young birds with no knowledge of the world, migrate vast distances with unerring accuracy has long mystified people.

If birds fly thousands of miles over unfamiliar terrain, what clues could they be using?!

Personally, I am fascinated by the idea that birds might use infrasonic sound as a navigation tool. I love this idea because it points to a fundamental principle of earth-sky-ocean interactions that you would otherwise never think about.

Did you know that air currents moving relentlessly over the earth's surface create sounds as they interact with key features? These interactions push fluids (both air and water) out of equilibrium, which creates harmonic disturbances (sounds) as the fluids ripple back into equilibrium. But we don't notice because these infrasonic sounds are extremely low frequency (0.1 to 20 Hz) and outside the range of human hearing.

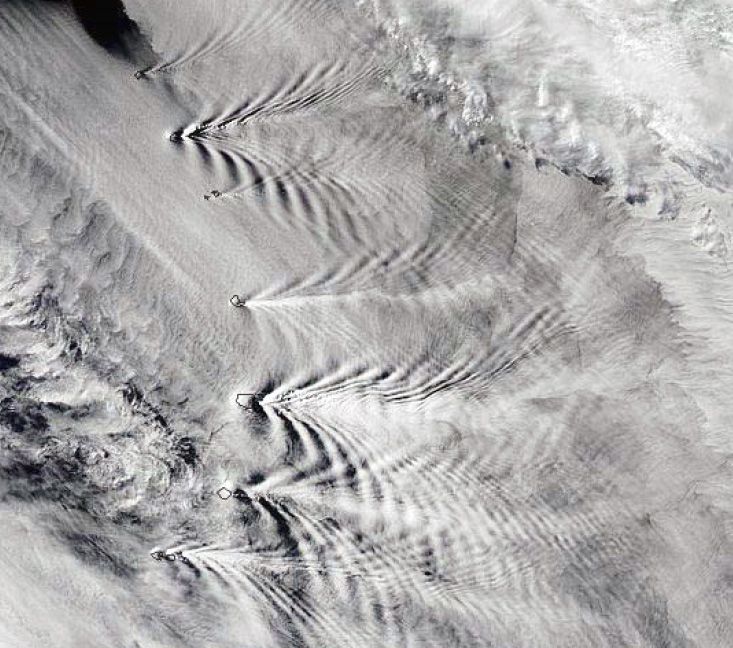

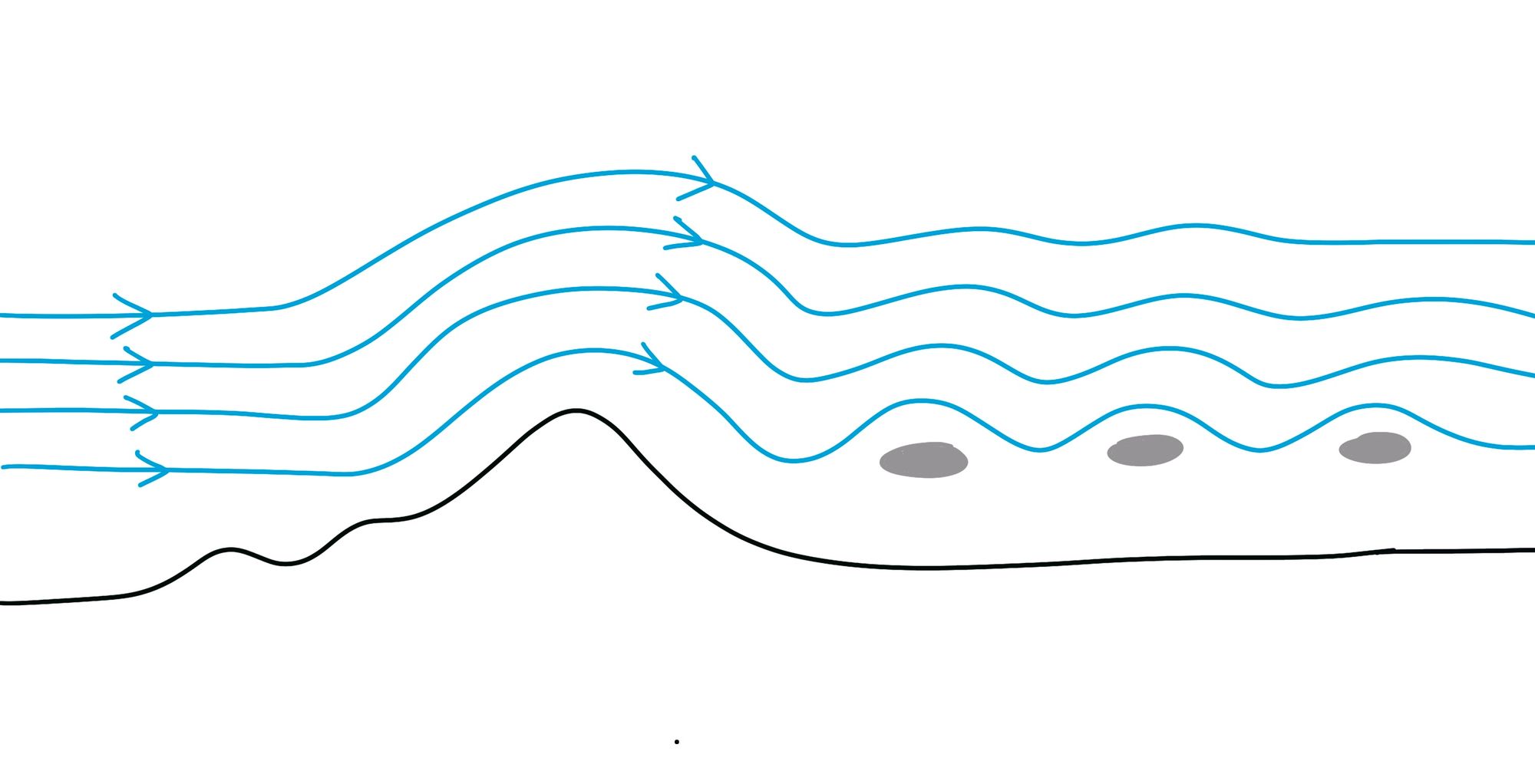

For example, a mountain range forces air currents to rise abruptly then sink in the lee of the range in a series of bouncing waves, called gravity waves. Another way to look at this is to imagine that wind passing over the lip of a mountain range is like blowing on the mouthpiece of a giant fipple (a wind instrument).

In addition, as wind passes over the ocean it creates a near-continuous hum as ocean waves interact with the atmosphere to produce low-frequency acoustic signals in the atmosphere called microbaroms.

Why might this matter to migrating birds?

This matters because infrasonic sounds travel hundreds of miles, which means these sounds resonate outward to create a vast web of auditory landmarks.

Imagine you are a bird migrating from Alaska to South America: This entire route follows a coastline as well as a long, continuous series of mountain chains that includes the Cascade Mountains, the Sierra Nevada, the Sierra Madre and the Andes. Theoretically, a bird listening to the sound of microbaroms in one ear and the sound of giant fipples in the other ear would never get lost.

Of course, birds use and follow a bunch of navigational clues, including magnetic compasses in their brains, polarized light projected into the sky at sunrise and sunset, and glimpses of passing landscapes. All these clues add together to give migrating birds a lot of information to work with.

What's most fascinating to me about migrating birds following infrasonic sounds is that this idea lies in the realm of conjecture. It's one of those amazing ideas that makes perfect sense, and explains the world in a way that I find magical, but it's never been proven.

Out of the world's roughly ten thousand species of birds, only five species have been studied for their perception of infrasonic sounds, and four of those species tested positive for hearing these sounds.

If the world is speaking loudly and clearly, and if birds have been migrating for hundreds of thousands of years, what do you think of the idea that birds have learned to follow these sounds?

Member discussion