Living in Tents

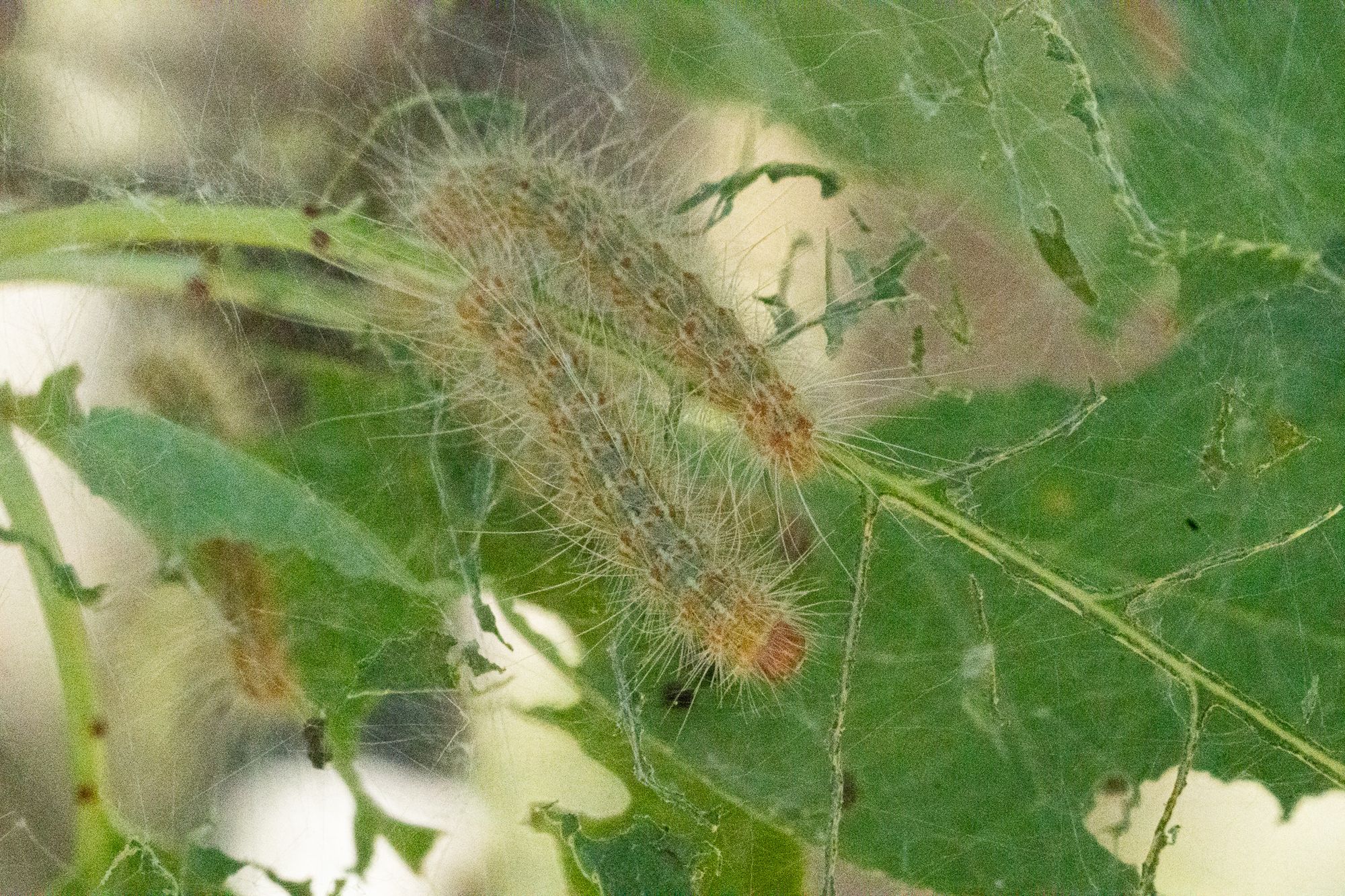

Have you noticed huge masses of silk in the trees this summer? You might recognize these as the work of tent caterpillars, but not realize what's going on inside these silken tents.

While adult tent moths are unremarkable insects, their caterpillars have astonishing social systems that rival those of ants or bees. In fact, scientists discovered in 1976 that these caterpillars were communicating with scent-marked silk trails to coordinate their complex, highly synchronized social behaviors.

Few of us would know or recognize the drab adults that emerge in July, fly under the cover of darkness, and die within hours of hatching. These adults never eat and live only to mate, with two-thirds of a female's body weight devoted to ovaries.

After mating, each female lays a single mass of 200-400 eggs near the tip of a branch and covers this mass with a shellac-like substance that protects the eggs from predators, parasites, and weather for the next ten months.

Amazingly, fully developed caterpillars stay inside the eggs all summer, autumn, and winter before emerging the following April or May.

Then, when the caterpillars hatch, things start getting interesting.

Tent caterpillars are the first leaf-eating insects to hatch each spring and their emergence is tightly synchronized with the unfurling of new leaves. This synchrony matters because the caterpillars can only thrive by eating fresh, young leaves and the pursuit of these leaves is what drives their complex social behavior.

As soon as all the caterpillars hatch from their egg mass they move as a group down a branch in search of a junction between twigs and begin weaving a web of silk. This "tent" serves as the caterpillars' home base and it continues to grow layer by layer as the summer progresses.

From this home base, the caterpillars engage in a behavior known as central-place foraging, which means they wander outward on 3-4 foraging expeditions each day then return to the home base after each foray.

The key function of central-place foraging is that it is an effective way of sharing information about scarce, hard-to-find food resources, and it's fascinating to understand how the entire colony benefits from this selfless sharing of information.

Each foraging bout is preceded by all the caterpillars emerging from the tent and gathering on the surface. As they wait for everyone to show up, the assembled caterpillars swing their heads from side to side, pulling out continuous strands of silk from glands around their mouths.

The collective action of dozens to hundreds of caterpillars laying down silk at the same time adds a new layer (or story) to the ever-growing, complexly-layered tent. As the silk dries it pulls taut and lifts the new layer up, so that by the time the caterpillars return to the nest they have a new space to move into.

One group of caterpillars appears to be the leaders of a colony and they trigger a mass exodus by splitting up and heading in different directions in search of food with followers close behind.

Every leaf on a tree or shrub has a different amount of water, nutrition, and physical toughness, and this keeps changing over time, which means the caterpillars have to continuously search far and wide for the best leaves.

As each leader looks for food it lays down a continuous thread of silk as an exploratory trail that is followed by the rest of the caterpillars. If the leader finds food, it eats its fill, then returns to the colony while laying down a recruitment trail that leads its nest mates to the food patch. Every subsequent caterpillar who successfully feeds at this same food patch contributes to this recruitment trail, amplifying the message and keeping the signal up to date.

If a caterpillar doesn't find food, it returns to the tent and sniffs each of the trails, looking for a fresh recruitment trail that leads to a patch of food.

All of this is done with unique odors that signal not only the type, but also the freshness of each trail.

You might think that any individual who finds a scarce food source would want to keep all the food for itself, but what's interesting about this strategy is that caterpillars instead share information about the best food sources with all of their nest mates.

The reason they do this is that they all have higher survival rates and grow much faster if they work together as a group. The more quickly each caterpillar eats a full meal, the more quickly each caterpillar gets back to the tent where they are safe from predators and parasites and where they can warm up together in the greenhouse-like atmosphere inside the tent.

By sticking together as a group, caterpillars grow about 50% faster, and those bigger caterpillars end up producing a lot more babies when they eventually turn into moths.

It's easy to dismiss tent caterpillars as a pest that damages trees, but I prefer to see them as a parable for our times. When times are tough, like they are now, wouldn't it be better if we all worked together?

Member discussion