Living in Film

Have you ever slipped on a slimy rock in the river? Congratulations, you've encountered one of the most successful forms of life that has ever existed on Earth!

Literally underfoot—and hidden in plain sight—we live in a world utterly shaped and dominated by biofilms. You might simply know biofilms as the slime that grows on wet rocks, or the dental plaque that forms on your teeth, or maybe you've read about them wreaking havoc in hospitals (where they cause 60-80% of all infections).

But biofilms first arose 3.25 billion years ago to protect the earth's earliest single-celled (prokaryotic) organisms and they've been around for a very, very long time. In fact, it looks like biofilms have existed since organic chemicals started assembling into primitive cells, and they are now woven into the fabric of life itself (for example, you'll find them lining and protecting the walls of your stomach and intestines).

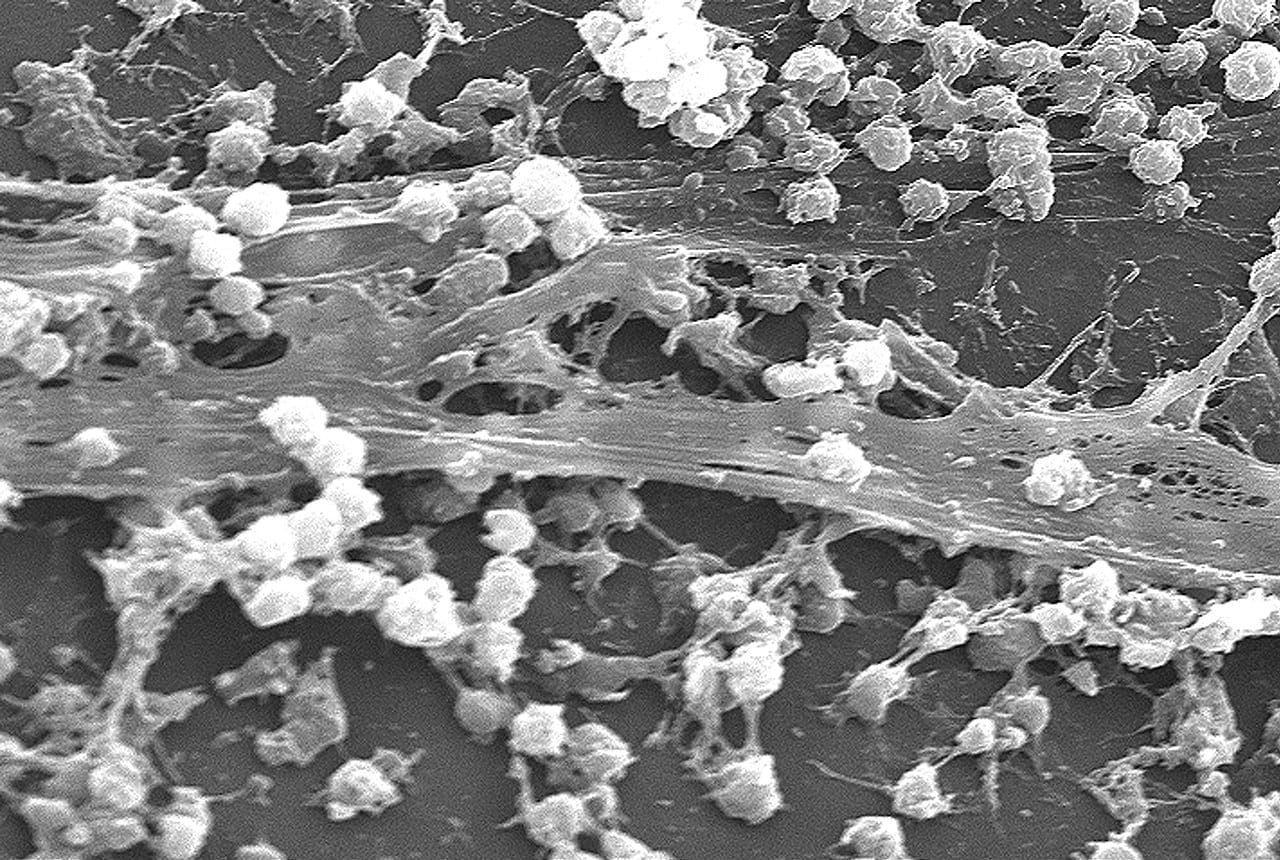

Biofilms are elegantly self-forming communities of life that arise as free-floating microorganisms (mostly bacteria) land on a surface. These first colonists may adhere to the surface using van der Waals forces or hairlike pili. By themselves these early settlers are highly vulnerable to dessication, extreme temperatures, and environmental agents like antibioitics, so they send out chemical signals (a strategy known as quorum sensing) to attract more bacteria to the growing colony.

What happens next is nothing short of spectacular because these microscopic colonies transform into something else. The bacteria themselves morph into new forms that are very different than their free-living selves, and together they build a biological collective that's more like a city, or a habitat, or an ecosystem —what we call biofilm.

Within this habitat, bacteria begin dividing up roles and working together for the greater good of the colony (hence the term synergistic microconsortia). For example, by working together as a colony, bacteria living in biofilm are 100-5000 times more resistant to antibiotics than they would be if they were living alone!

In one of my earlier newsletters this year, I touched on the topic of extracellular DNA, and this is where the story of biofilms gets weird. As soon as bacteria form one of these colonies, they begin actively secreting or breaking cell walls to release DNA into the environment around them.

These secretions of extracellular DNA become a living matrix that protects and facilitates the lives of the bacteria in a slimy goop that has been likened to berry jam, with scattered seeds (the bacteria) held in place by a much greater volume of sticky syrup (the extracellular matrix).

Not only do these secretions glue bacteria together and hold them onto the surface they live on, but they lock individual bacterial cells in place so they can begin developing unique roles and webs of relationships with each other. Incredibly, these relationships include horizontal gene transfer, which is a process in which genetic information is shared and recombined "horizontally" between entirely different organisms instead of being handed down "vertically" from parent to child.

Equally incredible, this extracellular matrix also functions as an external stomach that collects and digests foods, it acts as a network that allows bacteria to communicate and coordinate their behaviors as a collective group, and it serves as a firewall that protects bacteria from outside forces like dehydration, biological poisons, antibiotics, heavy metals, ultraviolet radiation, immune defenses, and many protozoan grazers.

As anyone who works in an industry (such as healthcare!) impacted by biofilms already knows, biofilms are outstandingly resilient and incredibly difficult to tackle. It's one reason why biofilms have stuck around for 3.25 billion years and become such a prolific part of life on earth!

Member discussion