Let's Talk About Anal Combs

Have you ever had the experience of walking in the woods on a summer day and hearing a pitter-patter that sounds like rain?

What you're hearing is millions of caterpillars in the tree canopy pooping out a never-ending shower of tiny fecal pellets that hit the leaves and ground as they fall.

However, there's more to this story than a bunch of caterpillars pooping on the ground!

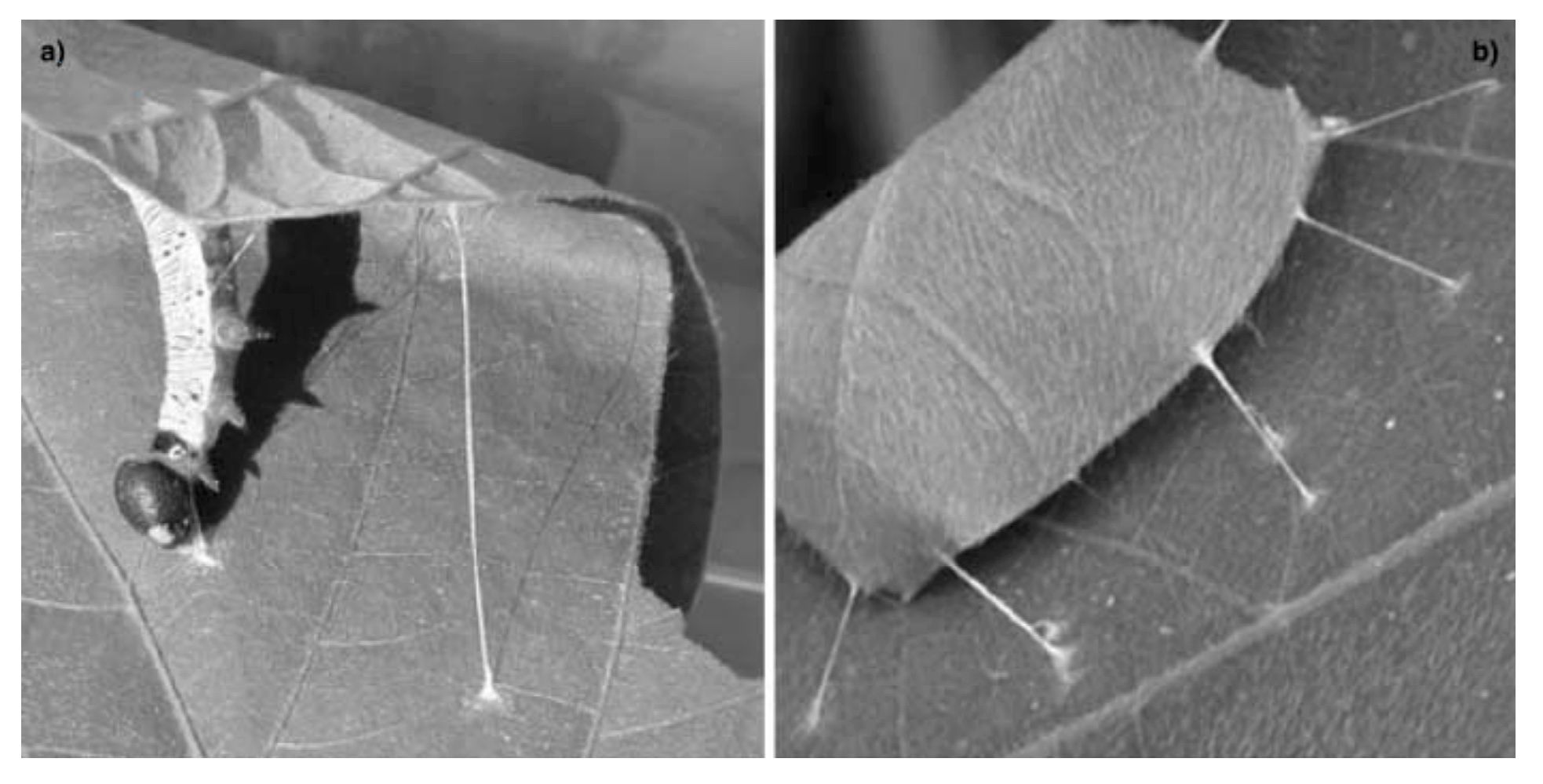

While many caterpillars simply walk around and poop off the edge of leaves as they feed, another group of caterpillars protect themselves by folding over, or rolling, the edges of leaves and sewing them shut with silk.

These so-called “leaf rollers” are a surprisingly large and successful group of caterpillars, including many species from 17 different families of moths and butterflies.

But leaf rollers also have a unique problem—they don’t leave their shelters, so they need a way to get rid of their poops.

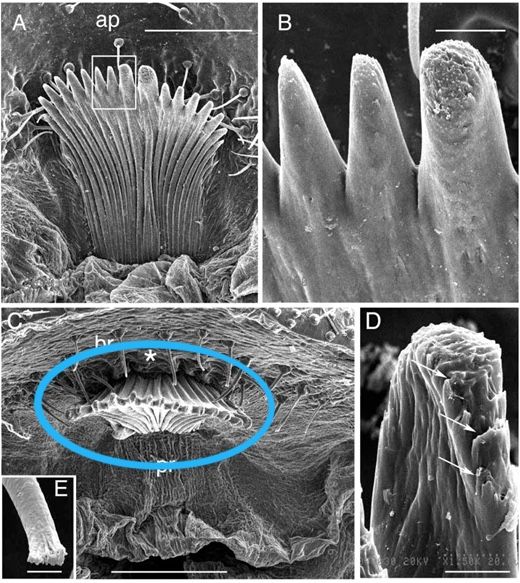

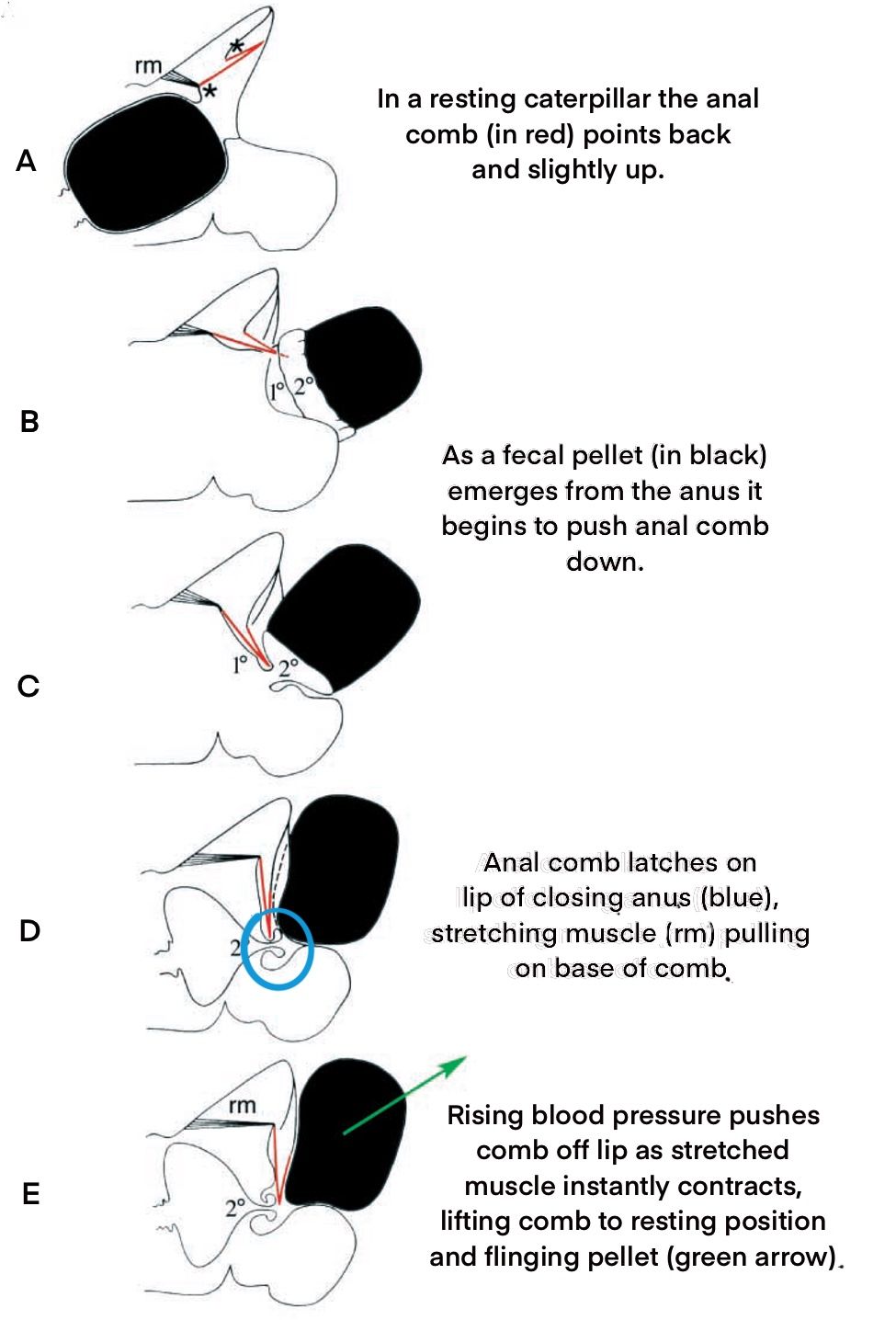

The solution is a special structure called an anal comb that sits on the hard plate that covers the caterpillar's rear end.

What happens when a caterpillar finishes pooping is that the fecal pellet momentarily sits on the comb as the comb helps close the anus with a unique latching mechanism.

The caterpillar then rapidly raises its blood pressure until the latch springs open and the comb flings the fecal pellet with tremendous speed—up to three feet away from the caterpillar!

An example of caterpillars flinging their fecal pellets (I find it amazing that 21,000 people have watched this 17 second clip!)

Depending on your point of view this may all be mildly interesting, but you might also be wondering why this matters?

If you are enjoying this post please share it with friends, and consider joining the growing numbers of followers who help support this newsletter by becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you for your support!

I love this story because it reveals an astonishing evolutionary dance that takes place between plants, herbivores, and predators (what scientists call a tritrophic interaction). This dance is subtle and happens on a very small scale, but it utterly shapes the green world we see every day.

Caterpillars are the earth's most abundant herbivores, so they exert tremendous pressure on plants, who are forced to shift their energy from growing and producing fruits and seeds to defending themselves whenever caterpillars are around.

And, as part of the dance, there is also a mind-boggling number of predators and parasites who specialize on finding super abundant caterpillars.

It is thought that there are more species of parasitic wasps than any other organism on earth.

This means that caterpillars must do everything they can to hide or protect themselves from an onslaught of attackers and, unfortunately for caterpillars, the plants they're eating are not their friends.

Plants don't like being nibbled on by caterpillars, so in an extraordinarily complex sequence of events called a "jasmonate signal cascade" (try Googling that if you want a real brain twister), injured plants produce over a thousand different volatile (airborne) compounds to warn other plants that caterpillars are in the neighborhood.

More importantly, these compounds send out a call for predators and parasites to rush over and help the plants get rid of their caterpillars.

This is a 9-minute video and it's not easy to watch but I include it here in case you want to see how this works.

These compounds are not only released from open wounds as caterpillars munch on leaves, but these compounds also accumulate in the intestines of caterpillars and become highly concentrated in caterpillar poops.

This means that every time a caterpillar defecates it leaves behind a scent bomb full of the plant’s warning signals that tells predators and parasites exactly where the caterpillar is.

With this in mind, it makes perfect sense why caterpillars have developed elaborate strategies for getting as far away from their poops as possible—and why you might experience a bit of "fecal rain" on your walks.

Member discussion