Going to See

"It is more important to live for the possibilities that lie ahead than to die in despair over what has been lost." Barry Lopez

A month ago, I found myself in a small independent bookstore and was startled to see a new book about Barry Lopez, a renowned writer who has loomed large in my life and work. It caught me off guard, especially because this was no ordinary book.

Going to See is that rare thing, a book of authenticity and warmth, full of deeply personal essays (some written in the form of private letters to Barry) from prominent writers and thinkers celebrating the inspirations, visions, and friendships that this thoughtful and generous man cultivated over his richly lived life. Reading these stories lifted and filled my heart and brought tears to my eyes in ways that few books do.

If you're not already familiar with the work of Barry Lopez, he was an Oregon-based writer who wrote many books, and countless essays, both fiction and nonfiction, exploring the edges of culture, landscape, and imagination. He received dozens of awards and honors for his prolific body of work, including a National Book Award for Arctic Dreams.

More than anything, Barry was an unrelentingly meticulous craftsman of words and ideas, a fact mentioned repeatedly and marveled at by his friends and colleagues in Going to See. He almost never spoke, or wrote, anything hastily, and in his public events he was that exceptional speaker who addressed every question with patient, profound consideration. Plus, he was generous to a fault, according to the writer Rick Bass he answered every letter he ever received, and year after year he would spontaneously call or write letters to people he had met only fleetingly, for no reason other than to offer words of inspiration and hope.

It is worth watching any of the videos about Barry on YouTube. Here is one I filmed of Barry in conversation with the writer Robert Macfarlane in Portland.

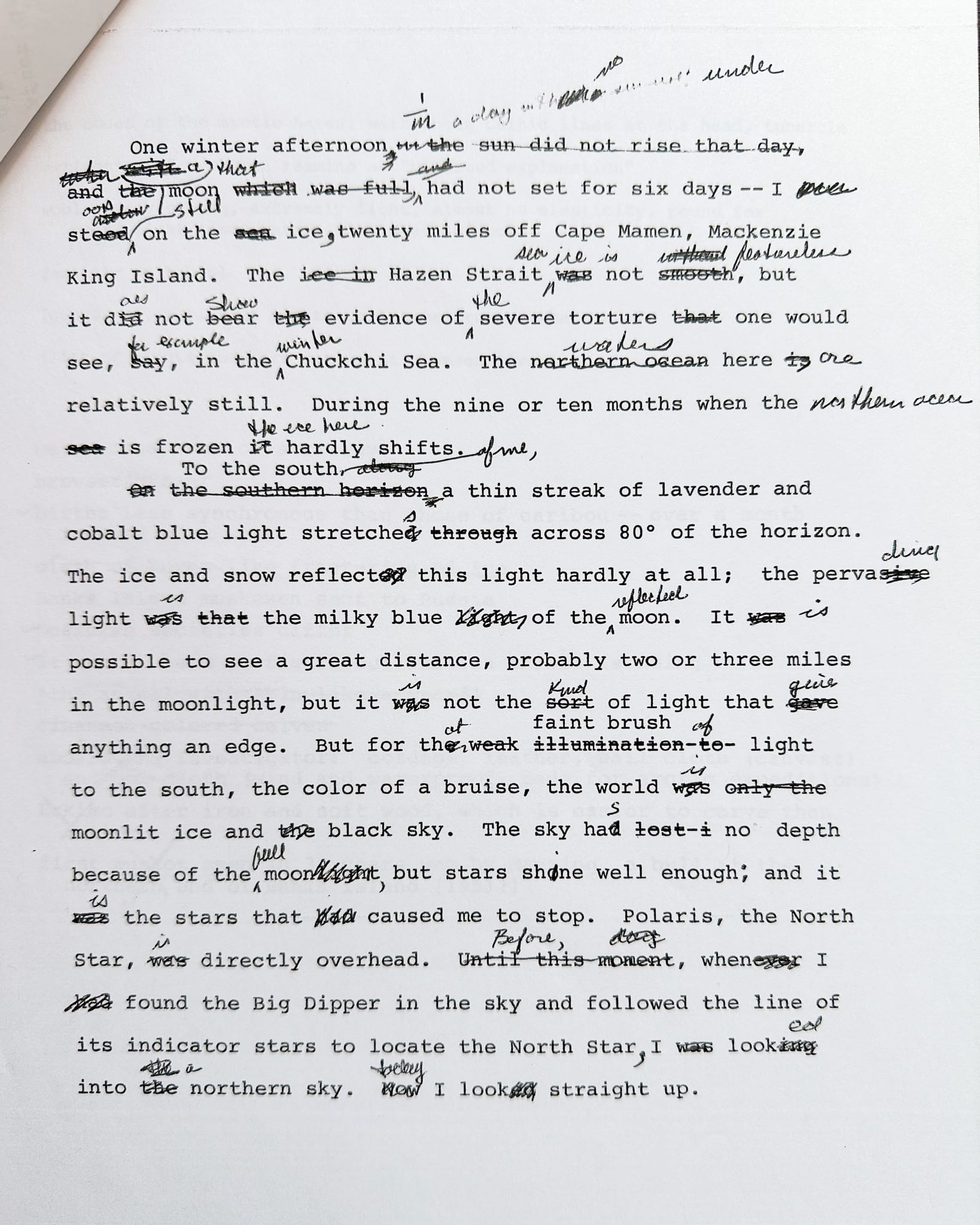

I was fortunate that my many, varied encounters with Barry included receiving a Formby Fellowship from Texas Tech University in 2006 to spend two months studying his papers in the University's Sowell Collection (which currently includes 300 boxes of Barry's archived papers). Being in his collection gave me a chance to document and trace Barry's meticulous craftsmanship firsthand (one day I hope to write up these research notes because they deserve to be shared).

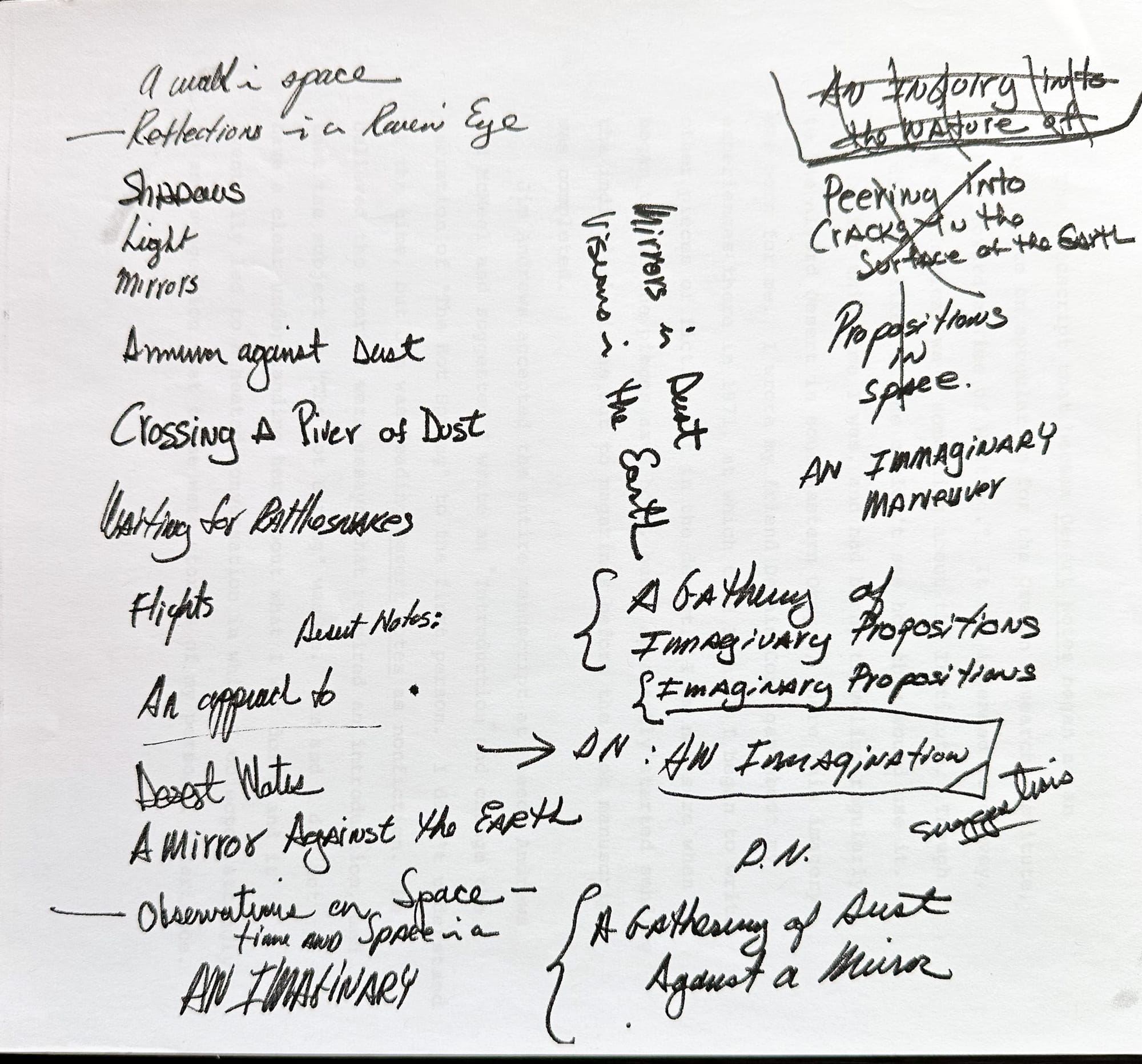

I've never seen anything like Barry's archives. Many of his best-known books and essays started as scribbled drafts on the backs of dozens of used envelopes that he carefully cut open and flattened out, while his more extensive projects included countless pages devoted entirely to sketching out the flow of the writing. For example, he might storyboard the narrative of an entire book, or write detailed and precise directions for how he was moving the reader's eye and attention, paragraph by paragraph, and section by section (what he called "movements"), as though he were conducting an orchestra of the imagination (e.g. look at this object—pause—turn to the right and pick up this object—pause—walk outside, etc.).

Examples from Barry's archives in the Sowell Collection: First draft of the first page of Arctic Dreams and mulling over potential titles for Desert Notes. Photos by David Lukas

Even more astonishing was the immense effort Barry put into every published work, including countless, heavily edited drafts, and exhaustive catalogs of themes and background materials. For instance, for a single chapter in Arctic Dreams he generated a 17-page list of topics and themes he wanted to cover. And when the complete draft of a book was finished, he would then retype the entire manuscript (on an electric typewriter!) half a dozen times or more. [On a side note, the owner of the typewriter repair store in Portland where Barry serviced his typewriters told me that Barry was the only person he'd ever met who wore out his typewriters and needed them repaired every couple months.]

But the most important aspect of Barry's work would have to be the values and compassion that he brought to life for all of us. In his own words he wrote of his "profound and common compassion for the predicament and challenge of being fully human." And in the words of Pico Iyer, "The light within was what guided him, and the light without was what he wished to bring to us."

Barry understood darkness—the blood of a kill, the terrifying edges of a known landscape, human atrocities—but at all times he asked himself, and each one of us, how we could be of service and how we could make our lives "a worthy expression of a leaning into the light."

Tragically, Barry died of advanced cancer in 2020, a few months after the massive Holiday Farm Fire burned the beloved landscape where Barry had lived for 50 years, along with the shed filled with Barry's personal journals, correspondence, and many critical papers. On so many levels, these losses are unimaginable, but as David Quammen writes in Going to See: "Here's the consolation, then: Barry is gone but his voice is not."

Member discussion