Flipping Water

All summer we've been out swimming in lakes—enjoying these watery worlds of fish and tadpoles, water striders and dragonflies. But did you know that these dynamic ecosystems are powered by a very important event that's just around the corner?!

Even if you're not familiar with this upcoming event, you are subconsciously primed to understand it from the moment you step into a lake or pond. Remember how that surface water feels so deliciously warm? And how, just below the surface, water feels bone-chillingly cold?

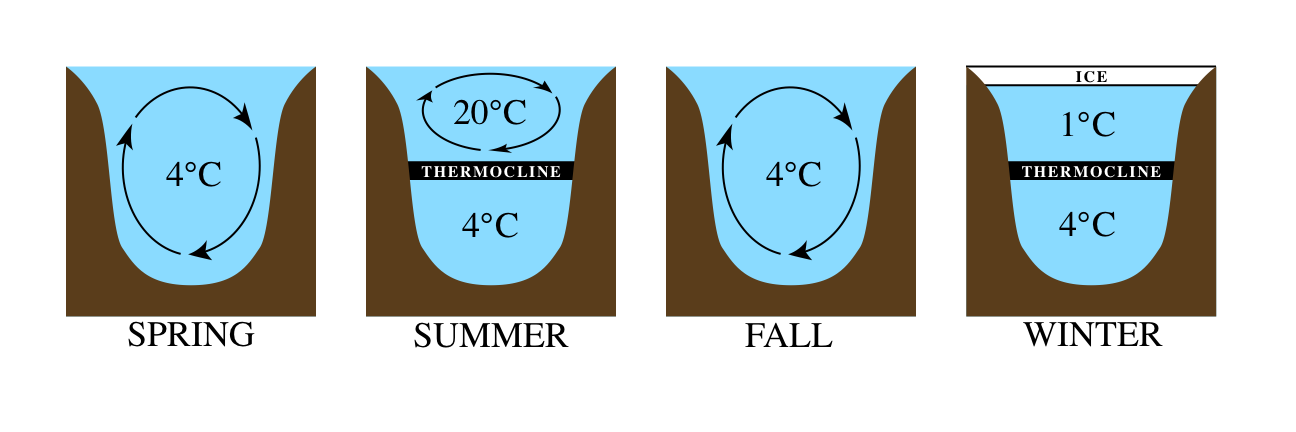

What's happening is that the blazing summer sun warms the surface water on a lake, and that warm water then expands and becomes less dense, which keeps it floating on top of the colder, denser water underneath it.

All this makes perfect sense, but you may not realize that this stratification into layers—with a lid of warm water covering an entire lake and trapping cold water underneath—can become so strong that it traps the nutrient cycles of a lake.

Of course, these layers have names, with the uppermost warm layer being called the epilimnion, the cold bottom layer being called the hypolimnion, and the transition zone in between being called the metalimnion (or the thermocline).

With warm sun powering photosynthesis in plants at the surface and gentle winds mixing oxygen into the water, the surface layer ends up becoming oxygen rich and full of life. But this layer also concentrates nutrients, including runoff from agricultural fields, and these can trigger outbreaks of algae that turn toxic.

At the same time, the deep cold waters in a lake become starved for oxygen (anoxic) because oxygen-hungry bacteria feast on organic matter sinking from above and grow in numbers.

There are many, many other complex chemical and ecological processes happening in a lake, and each lake experiences different conditions, but in general thermal stratification divides a lake into two very different temperature, oxygen, and nutrient zones that don't overlap. And this is a serious problem because at some point one or more resources will become limited and potentially kill many of the organisms living in that portion of a lake.

However, a big change happens as summer fades and temperatures begin to drop. As surface waters cool, their density changes, causing them to sink and mix with deeper waters. This eventually evens out the temperatures (hence water density) in all parts of a lake, weakening stratification to the point where strong fall and early winter winds can easily "flip" the lake's waters.

This flipping, also known as lake turnover, is critical to the health of a lake because it redistributes oxygen and nutrients and recharges a lake.

Each lake flips in a different way—with some lakes flipping once a year, or twice a year, and other lakes flipping regularly; while other lakes take years, decades, centuries, or millennia (!) to flip—but that vibrant, healthy lake you love and enjoy is only possible because it flips at some point.

Member discussion