Eating Sunspots

Today's newsletter started with the classic story of the up and down cycles of snowshoe hare and lynx populations, but I had no idea I was going to literally fall down a "rabbit hole" into a story far more complex than my brain can comprehend.

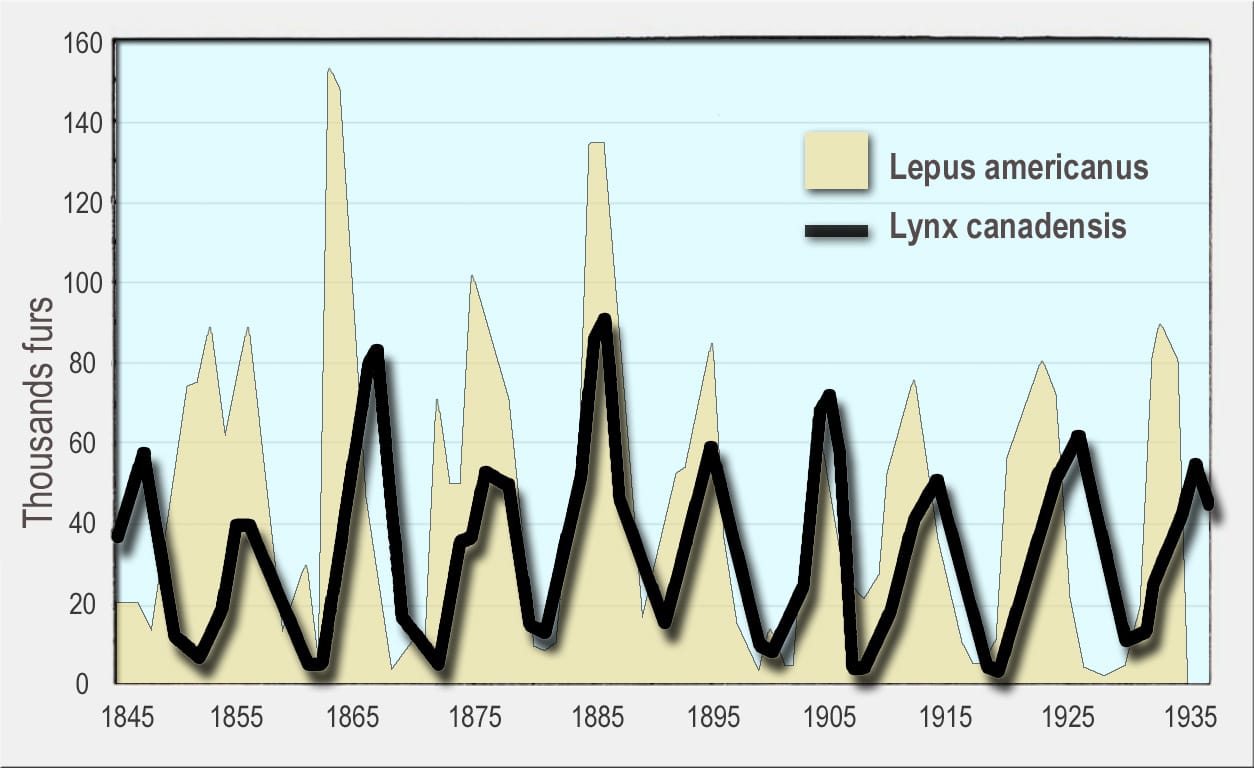

Let's begin by setting the stage. In the 1930s a scientist realized that fur trapping records from the Hudson Bay Company, stretching back to 1671, provide a remarkable insight into long-term patterns in animal populations. In particular, he focused on snowshoe hares and Canadian lynx and discovered a consistent, repeating pattern with hare populations peaking every 9-11 years and lynx populations peaking up to two years later.

This has become the textbook example, taught in every high school and college biology class, of what's called the Lotka-Volterra equation, in which predator-prey populations rise and fall in relation to each other. In other words, when prey populations increase then predators start feasting and having more babies, but when predator populations increase they eat all the prey so prey populations crash and then predator populations crash.

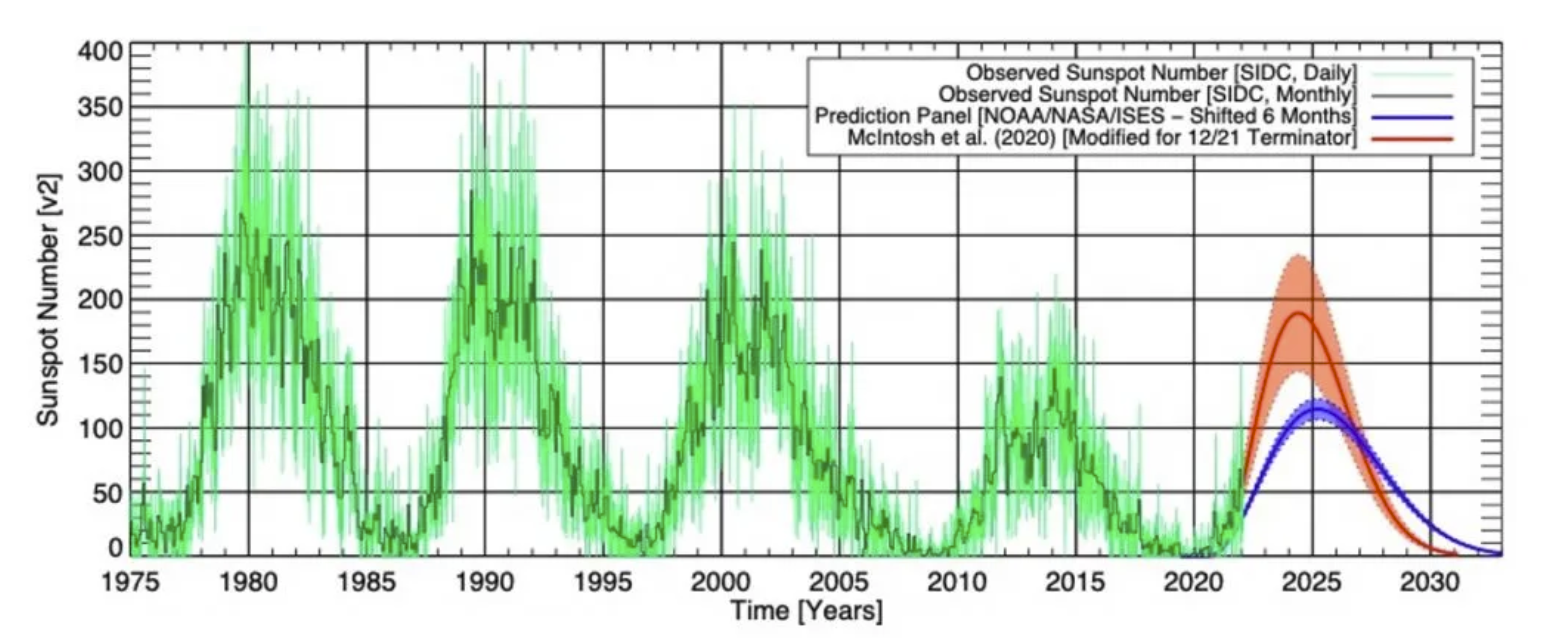

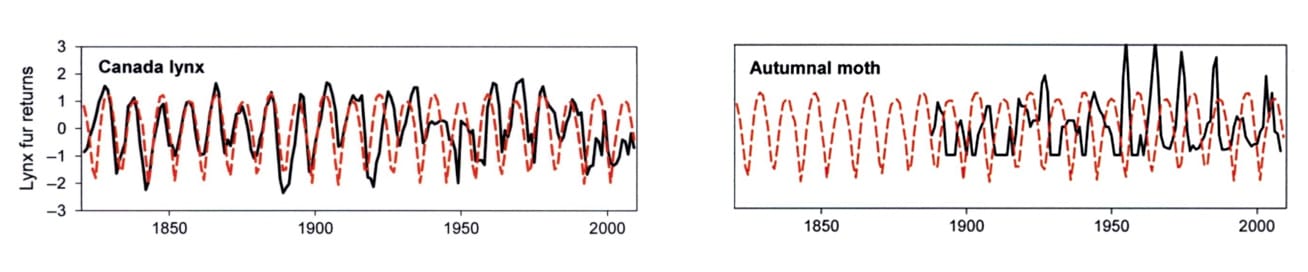

This is a neat and tidy story, easily taught and easily understood, but the question that has long baffled biologists is what mechanisms are driving these cycles. There are now hundreds of papers exploring this question but one intriguing hypothesis is that hares (and other boreal forest herbivores such as moths) are responding to the 11-year sunspot cycle.

Because hare populations peak at the same time across all of Canada and Alaska, it seems like they are responding to some universal external cue, and it turns out there's a remarkable degree of overlap between hare populations and sunspot activity. Although some scientists have dismissed this hypothesis because the overlap doesn't always line up, I read a lot more papers and found that the story is far more complicated than I imagined.

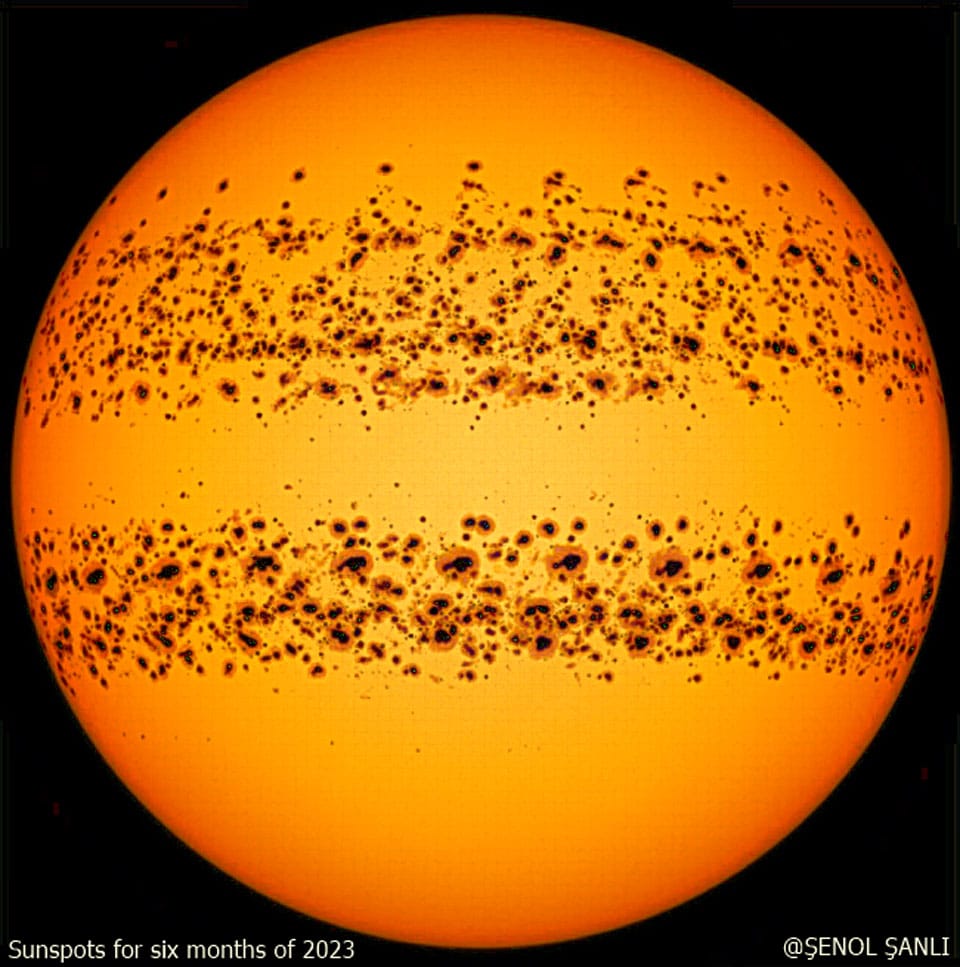

So why sunspots? Well, it turns out that during periods of high sunspot activity (and it just so happens that 2025 is the peak year in Solar Cycle 25), the Earth's ozone layer thickens and less UV radiation reaches the Earth's surface. Conversely, during periods of low sunspot activity, the ozone layer thins and more UV radiation reaches the Earth.

There are two main reasons why plants need to protect themselves. They need to protect themselves from herbivores by producing indigestible compounds, and they need to protect themselves from ultraviolet (low energy) radiation and cosmic (high energy) rays that break down DNA and can lead to death.

Unfortunately for plants, both defense mechanisms use the same metabolic pathways so plants have to make a choice. In years with less UV radiation plants focus on protecting themselves from herbivores, but in years with high UV radiation they switch to protecting themselves from radiation, which leaves them exposed to herbivores, and this is when hare populations explode.

Although hare and lynx populations generally mirror each other, they occassionally get out of sync. However, every 80-90 years there's a recurring peak of extremely high solar activity called the Gleissberg cycle that pushes their populations back into synchrony, so even if sunspots don't correspond to every population swing they still seem to account for the larger pattern.

It's still not clear whether sunspots are the primary driver of hare and lynx population swings, and the story gets much more complicated as soon as you factor the Moon into the story.

This is where my brain starts to short circuit because the physics and math of planetary orbits goes far beyond anything I understand. But basically, there are specific alignments of the Sun, Moon, and Earth, known as Luni-Solar Oscillations, creating another layer of cycles that recur every 9 and 18 years.

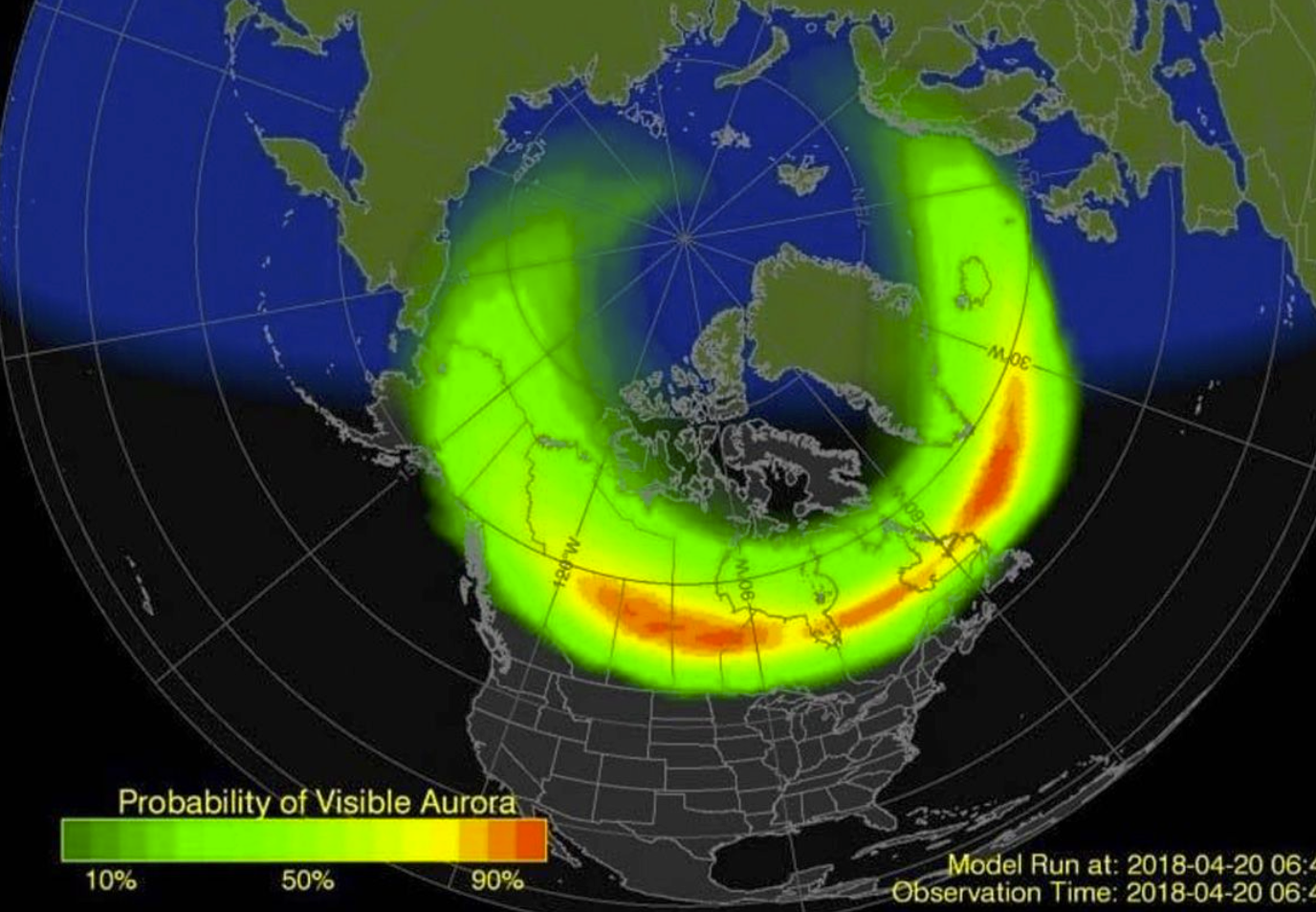

This matters because during different phases of the Moon's orbital paths the Moon pushes and pulls the Earth's magnetic fields and exposes the Earth to varying levels of cosmic rays and solar winds (which we sometimes see as an aurora borealis at northern latitudes). When cosmic rays strike the Earth's atmosphere they break down into subatomic particles called muons and, depending on the alignment of the Luni-Solar Oscillation, very high numbers of muons may descend on Canada and Alaska and force plants to mobilize their defense mechanisms, adding another cycle on top of the sunspot cycle.

As you can tell, there are layers upon layers of cycles creating complex patterns, but the core principle is very simple: Life on Earth is completely dependent on sunlight, so it makes sense that recurring patterns in solar activity will show up in cycles of life such as the population swings observed in hares and lynx. The same can be said about cosmic rays because life on Earth is dependent on the atmosphere protecting us from harmful rays, so recurring patterns in cosmic rays getting through the atmosphere will also have a similar impact.

It's a lot to think about.

Member discussion