Betting on the Bud Bank

Every year, plants produce untold trillions of seeds, then scatter these seeds far and wide across the earth’s surface. This mass of seeds, and the potential life they embody, is known as the seed bank.

While they carry the promise of a new generation and can sit in the soil for decades, or hundreds of years, waiting for the right conditions, seeds are a risky strategy for a host of reasons.

The merging of genes from separate parents promotes genetic diversity, but it also creates untested genetic combinations that are not proven to work. Furthermore, seeds are cast adrift with no connection or support from parent plants so they are solely reliant on a tiny packet of energy inside the seed.

You might not realize it, but a key principle of life on earth is that a huge number of plants utilize a different strategy that doesn't involve flowers and seeds—a strategy that entails storing extra carbohydrates in special underground structures, then using this stored energy to produce new buds that arise from these storage organs.

These types of plants are called geophytes ("earth plants"), and so many plants use this strategy that in 1977 the preeminent plant ecologist John Harper coined the term bud bank to describe the incalculable numbers of storage organs and buds waiting in the soil.

You may have never heard of a geophyte, but they are among our most familiar plants because these carbohydrate-rich storage organs include important foods such as carrots, beets, potatoes, onions, garlic, and many other common vegetables.

This strategy has arisen so many times, in so many types of plants, that plants have developed an astonishing variety of underground storage organs and mechanisms by which buds arise from these organs.

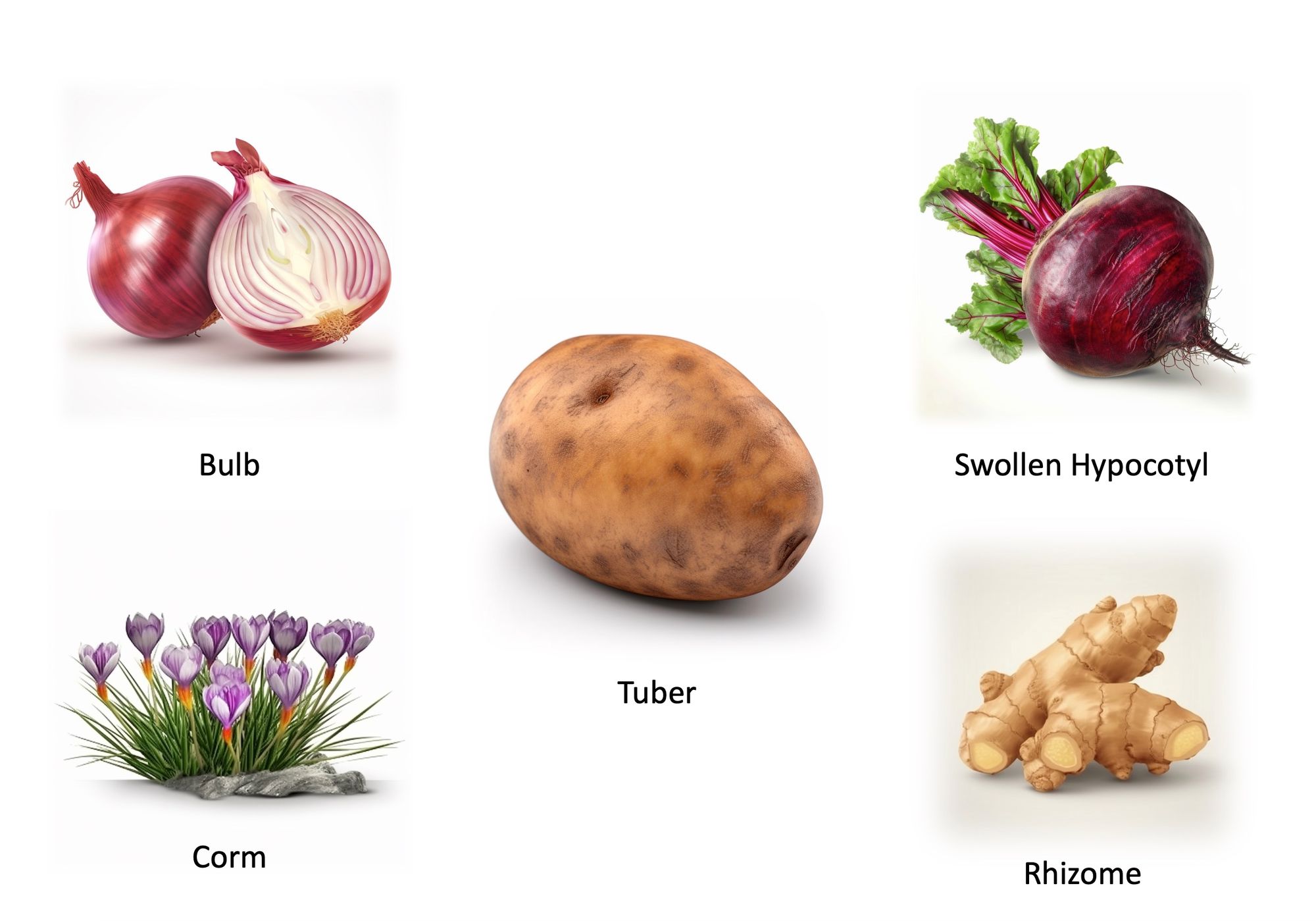

Rhizomes, bulbs, tubers, and corms are just some of the very different ways that plants store food and produce dormant buds. For example, a bulb, such as an onion, is a highly compressed stem wrapped in swollen leaves that store energy; while a tuber, such as a potato, stores energy in a root rather than a stem.

Ecologically, the bud bank is critically important because it’s the key way that ecosystems stitch themselves together and endure disasters or extreme seasonal changes.

In habitats such as grasslands, forest understories, and arctic tundra, so few seeds have a chance to sprout that the bud bank is literally the only way these habitats survive over time.

For example, in the tallgrass prairies of the Great Plains, competition for space is so intense that over 99% of all grass stems grow from the bud bank and new seeds have almost no chance of success.

There are many advantages to investing your reproductive efforts in a bud bank rather than a seed bank. Storing extra energy and dormant buds in a safe, underground location ensures that plants can immediately sprout and recover after fire or other disturbance, which means these plants will utterly dominate other plants that rely on seed production.

If plants can’t sustain themselves by recruiting new seedlings, then having a bud bank is the only way these plants will persist. In fact, plants that use underground storage organs can become even more expansive by abandoning old root systems and branching out into new root systems as clones of themselves (learn about the roots of aspen trees).

Buds that arise from parent roots also possess the unique advantage of having a genetic composition which has been tested and proven to work for the site they're growing on. Not only that, but young buds have the continued support of their parents through their connected root systems, which can be a critical advantage over tiny new seedlings trying to survive on their own.

Scientists have only recently begun to understand the huge range of overlooked wild plants that use this strategy and study the critical ecological value of these plants, but looking at plants through this new lens might change how you see the world.

Member discussion