A Dangerous Journey

One of the earth's greatest wildlife spectacles is just now getting underway, and the scale of it is staggering.

I'm talking, of course, about the spring bird migration.

There's a lot we could say about the science of bird migration—for instance, last fall I wrote about how birds use infrasonic sound as a navigation cue—but today I simply want to bask in the glory of this event.

Bird migration is truly a phenomenal event, and it represents a massive movement of biomass winging back and forth, like a tide going in and out, between the equator and the arctic. In the United States and Canada alone, an estimated 6-8 billion birds migrate north in the spring, then south in the fall.

Bird migration is amazing!

Migration, both spring and fall, is a long and perilous journey with many incredible stories. For example, ruby-throated hummingbirds who weigh as much as three paper clips make a 20-hour, 500–900-mile journey across the Gulf of Mexico with their wings beating 50-70 times per second and hearts pumping 1250 times a minute.

Consider juvenile bar-tailed godwits that make a nonstop flight 7000-8000 miles over the Pacific Ocean from Alaska to Australia, two months after hatching. Or tiny blackpoll warblers who migrate 2000 miles over the open ocean from New England to South America.

As I said, this is an exhausting and dangerous journey, with huge numbers of migrants dying enroute. But ultimately, what matters is that for many different reasons, evolution favors birds that migrate over birds that stay put.

It's also worth remembering that migratory patterns are snapshots in time. Formerly sedentary birds can become migratory, and migratory birds can become sedentary. For example, nonmigratory house finches imported from California to New York in the 1940s developed a migratory strategy in response to New York winters within 20 years. And it's believed that many migratory patterns in the Northern Hemisphere were shaped by Pleistocene glaciers that were widespread until 12,000 years ago.

It can be difficult to appreciate the full scale of this migration from our limited perspective as humans standing at one spot on the ground. We might notice groups of warblers or juncos moving through our yards, or we might spot flocks of ducks flying overhead.

If we're lucky, we might even experience a "fallout" when hundreds or thousands of exhausted birds stop to feed and rest at the same time. Or we might be outside on a day when lines of migrating geese are visible from horizon to horizon.

But we also live in a glorious time when advanced tools allow us to see migration in new, and surprising, ways. Miniature transmitters attached to birds, networks of radar stations, and thousands of people sharing their daily observations are all giving us an increasingly sophisticated understanding of bird migrations.

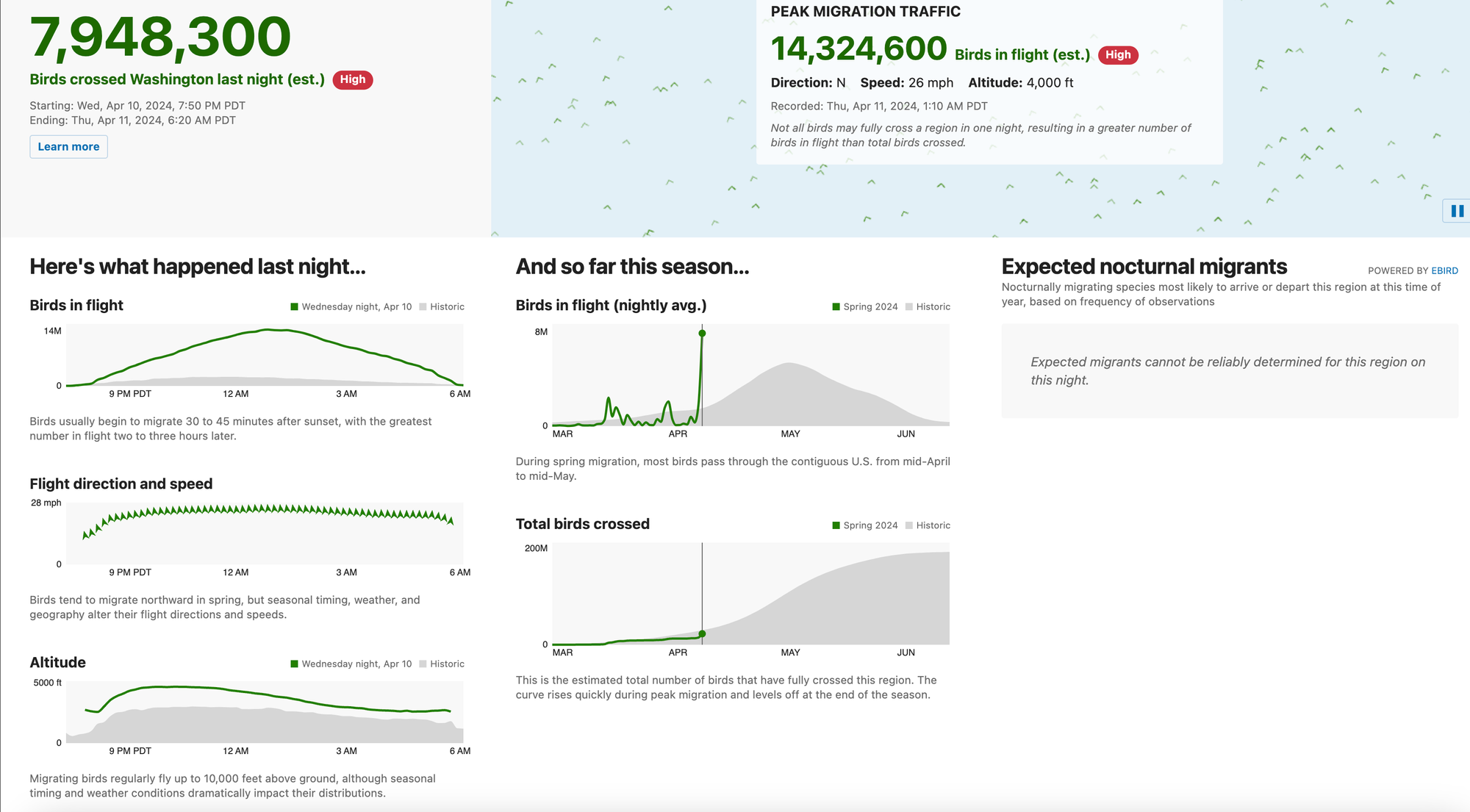

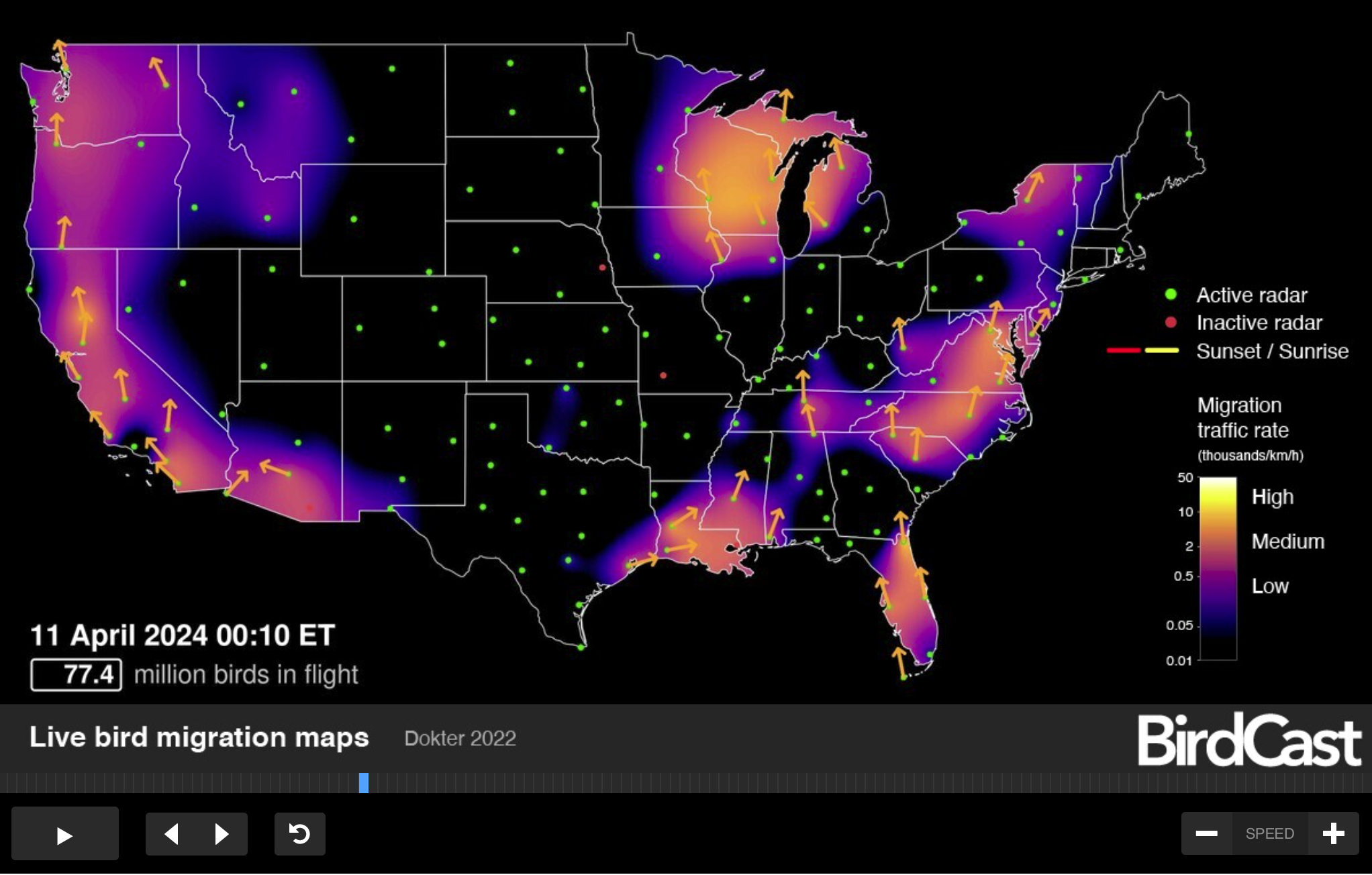

If you've never done this before, I encourage you to visit the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology's BirdCast website. Their maps are incredible and range from maps that forecast how many birds will be migrating over the next three days, to detailed readouts of what's going on in your state.

Particularly impressive are the interactive live bird migration maps that show how the patterns of birds migrating over the United States have changed every ten minutes over the past 24 hours. You can watch this as an animated video or click the arrow to watch it frame by frame. It's especially fascinating to observe how migrating birds respond to sunset and sunrise!

Spring migration is an exciting time of year, so however you can, I hope you get out and have a chance to glimpse part of this spectacle over the next six weeks!

Member discussion